THE FAIREST FORCE

4. MOBILISATION

*****

Immediately prior to the outbreak of the Great War Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service was just 298 members strong, the largest it had ever been.[36] Although it could not be anticipated at that time how long the war would last or how many nurses would be needed to staff the various medical facilities, the War Office understood that rapid initial expansion was vital.

Dame Ethel Becher, QAIMNS, Matron-in-Chief at the War Office, 1910 - 1919

THE MATRON-IN-CHIEF

In August 1914 the Matron-in-Chief of QAIMNS, Ethel Becher, sat behind her desk at the War Office assisted by her Principal Matron Maud McCarthy. Miss Becher was on the verge of retirement and her own period of service as Matron-in-Chief, a four year tenure, was due to end on 22nd September 1914. In the event that was set aside and she continued in her position, finally retiring on the 5th August 1919 and becoming, due to circumstances beyond her control, the longest serving Matron-in-Chief in the history of the Service.[37] During the week prior to mobilisation Miss Becher was already busy making arrangements for war. She recalled some of the ‘regular’ QAs from overseas. She knew that these women were needed to form the heart of the wartime service though it would take some time for them to arrive. She sent telegrams or letters to retired or resigned members of QAIMNS asking if they could return and, if so, giving them orders.

THE RETIRED MEMBER

Clara Chadwick was one of the 168 women who retired from QAIMNS in the years between 1902 and 1914. She was a well-respected and long-standing member of both QAIMNS and before that its predecessor, the Army Nursing Service. She was a well-bred woman, born and raised in relative luxury at her family home, New Hall, Sutton Coldfield. When her feckless father lost his house and fortune to gambling she was forced to make her own way in the world and trained as a nurse at Guy’s Hospital in London before joining the Army Nursing Service in 1886. She went on to serve at home and abroad for twenty-five years, finally retiring in 1911 to a flat in Hounslow, Middlesex, near to the barracks that had been her final place of work. After the war she wrote:

On Saturday August 2nd, 1914, I went to the War Office to see the Matron-in-Chief to volunteer for active service and I asked to be sent to the Front.[38] The Matron-in-Chief told me to hold myself in readiness, and on August 5th 1914, I received a telegram from her, ordering me to join at the Military Hospital, Hounslow, for duty, on August 7th.[39]

Clara Chadwick served throughout the war, finally retiring for a second time in September 1920, the whole of her wartime service being at Hounslow Military Hospital. In similar fashion, one hundred retired or resigned members of QAIMNS also mobilised, many of them older women, and many of them served at home, often taking charge of some of the United Kingdom’s larger camp hospitals. The retirees among them were fortunate as they continued to receive retired pay in addition to receiving the usual rates throughout their service – being paid twice had something to recommend it.

Even before war was declared, Ethel Becher had to consider the formation of a nursing force to support the British Expeditionary Force overseas and decide who she would trust to take charge in situations completely unknown and untried. The obvious choice was her deputy and Principal Matron Maud McCarthy and between them they set about organising groups of nurses to be attached to the General Hospitals that were being sent to France. At that point there was a restricted pool to choose from; members of the regular service, two hundred of the permanent QAIMNS Reserve and the women of the Civil Hospital Reserve. Of this last group she knew little, having no clue as to their names, personalities or experience. In that respect she had to trust the skills of the matrons of the hospitals to which they belonged. Those matrons were asked to arrange for the immediate mobilisation of their staff members and individual women were given orders where to join. Exact details of the process are not known but its speed suggests that the hospitals were already well supplied with blank copies of War Office contracts and understood what was expected of them. Ethel Becher had no authority or control over the Territorial Force nurses; they were entirely separate and their comparatively larger numbers were not immediately available to her.

THE QAIMNS RESERVIST

One of the QAIMNS Reserve members ready and waiting was Kate Luard, who later became one of the few trained military nurses to write and publish an account of her wartime service. She was forty-two years old and had been a member of both Army Nursing Reserves since 1900, seeing service in South Africa during the Boer War. For eight years prior to the war she worked at the Berkshire and Buckinghamshire Sanatorium at Peppard Common.[40] She was sent immediate orders for mobilisation, signed a contract with the War Office on the 6th August 1914 and was allocated to No.1 General Hospital, at that time in Dublin preparing to embark for France. It is known from the unit war diary of the hospital that officers, men and the nursing staff arrived in Dublin on August 11th and by the following morning that one Matron and 42 Nursing Sisters were accommodated in the Hotel Metropole, Sackville Street. Within six days Kate Luard had left her regular employment, got kitted out, travelled to Dublin and joined her hospital. That was the situation for all of the 200 members of the pre-war QAIMNS Reserve who mobilised, though most didn’t have to go as far as Dublin to embark. By 8 p.m. on the evening of the 18th of August she was on board the ‘City of Benares’ waiting to leave, and wrote:

We had a great send-off in Sackville Street in our motor-bus, and went on board about 2 p.m. From then till 7 we watched the embarkation going on, on our own ship and another. We have a lot of R.E. and R.F.A. and A.S.C. and a great many horses and pontoons and ambulance waggons; the horses were very difficult to embark poor dears. It was an exciting scene all the time. I don’t remember anything quite so thrilling as our start off from Ireland [41]

The writer of No.1 General Hospital’s war diary, a doctor of the Royal Army Medical Corps, was a little less enthusiastic, remarking

... the fact that 43 Nursing Sisters accompanied the hospital was altogether overlooked by the embarkation staff until just the evening before sailing, otherwise everything connected with the embarkation went off without a hitch.a comment that does highlight a rather dismissive view of the nursing staff by members of the RAMC.[42]

THE PRINCIPAL MATRON

By the time that the ‘City of Benares’ and No.1 General Hospital reached Havre on the morning of August 20th, other nurses had been in France for nearly a week. When the nursing services earmarked for France were put in the charge of Maud McCarthy they were put in safe hands. She was an Australian by birth and trained as a nurse at The London Hospital, Whitechapel; she saw service in South Africa and was a member of QAIMNS from its earliest days in 1902. When the Great War started she was not a young woman being fifty-five years old in 1914. As Dame Maud McCarthy she finally returned home in August 1919 after five years in France and is said to be the longest serving head of any single department in the British Army to retain their post throughout the entire war.[43]

Dame E. Maud McCarthy, Matron-in-Chief, France and Flanders, 1914 - 1919

THE CIVIL HOSPITAL RESERVIST

Isabelle Eugenie Marie Barbier came from a large French family domiciled in the UK and she was born in Cardiff on 24th July 1885. Her father, Paul Barbier, arrived in England in the 1870s to work as a schoolmaster and by turn of the century held a position as Professor of French at University College, Cardiff. Isabelle trained as a nurse at Bristol Royal Infirmary between 1910 and 1913 and at the declaration of war was still working in Bristol as a trained nursing sister. Her name was one of those entered on the roll of nurses at her hospital who were willing to be part of the Civil Hospital Reserve, and on the 5th August 1914 she mobilised and signed a contract with the War Office to serve at home or abroad for a period of one year. Her signature was witnessed by her Matron at Bristol, Miss Baillie, showing that even at that early stage the civil hospital matrons were familiar with the procedures involved and in possession of the correct forms. She was one of the forty-three women allocated to No.2 General Hospital who within three days were at Aldershot preparing to embark for France. Isabelle Barbier had four older brothers who served with the French Army during the war, but at that time she could not have envisaged the exact path that was mapped out for her as a British nurse in wartime.

When Principal Matron Maud McCarthy disembarked at Havre on the 15th August she was on her own. She had no assistant, no office, not even a desk. Her entry in the war diary that first evening reads, ‘Reported myself at DDMS office. DDMS not there – saw Major Forest. Evidently was not expected.[45] She had no real idea of the military situation or where the hospitals were to be opened. Although an educated and experienced woman she found herself dealing with an unknown situation in a foreign country and with little support. What she needed more than anything was another pair of hands and someone who understood the language. Two weeks later, probably feeling slightly desperate, she remembered that on the Comrie Castle there had been a bilingual staff nurse with her party of nurses and sent for her. Within a couple of days Isabelle Barbier had arrived and was settled in as her secretary, her assistant, her colleague and her right-hand man, a post that she kept for the next five years. Isabelle Barbier was a devout woman who worked tirelessly in the organisation and administration of the nursing services in France and Flanders. For her war service she received the MBE, the Royal Red Cross and was mentioned three times in despatches. After the war she entered a Catholic religious community becoming a nun with the Order of St. Dominic at Stone in Staffordshire where she lived out a very long life, dying in 1982 at the age of ninety-six.

Because the Civil Hospital Reserve was already set up pre-war and in the hands of civil hospital matrons who were organised and experienced, members were mobilised very rapidly and a great many went to France with the first of the General Hospitals. A total of 374 members of the CHR were awarded the 1914 Star for service in France and Flanders prior to the 22 November 1914, which emphasises how wise the War Office were in setting up the service and what a great asset it proved from the earliest days of war.[46] Although there had been an agreement when the service was set up that any woman who mobilised would have an assurance of an equivalent post waiting for her when she returned, no-one could have anticipated the length of the war. Over the course of the next four years the majority of the women had ceased being members of the CHR and signed new contracts as members of QAIMNS Reserve. In the event the hospitals could not wait that long for them to return. Service records for these women often show some confusion as to their exact affiliation with documents allocating them to different services at various times.

Within a few days of the outbreak of war, hundreds of trained nurses in the UK were clamouring to join the military nursing services. Because of the tremendous pressure on the War Office at that time it was decided that all nurse recruitment would be handled by the British Red Cross Society from Devonshire House and they interviewed and screened all applicants both for their own service and for the War Office.[47] Nurses were keen to be part of the war. One thing that had to be considered was that the number of fully-trained nurses in the United Kingdom was limited – it was far from a bottomless pit, and as it took three years to train a nurse the supply could not be increased in the short term. During the early days of the war many nurses went overseas under their own steam to Belgium, to areas of France not under British control and also further afield. That could not be prevented but the United Kingdom’s civil hospitals had to be protected against losing too many of their trained and experienced staff. It was a delicate balance and efforts were made for a controlled expansion. One problem to emerge from the BRCS being given responsibility for recruitment was that the qualities they considered suitable in a trained nurse didn’t necessarily meet War Office requirements, the latter having always insisted on the highest standards of education and training. Within a few months the War Office decided to do its own recruiting and thereafter applicants were asked to apply directly in writing to the Matron-in-Chief at the War Office.

Notice in British Journal of Nursing, August 1915, but present on a regular basis

THE TERRITORIAL

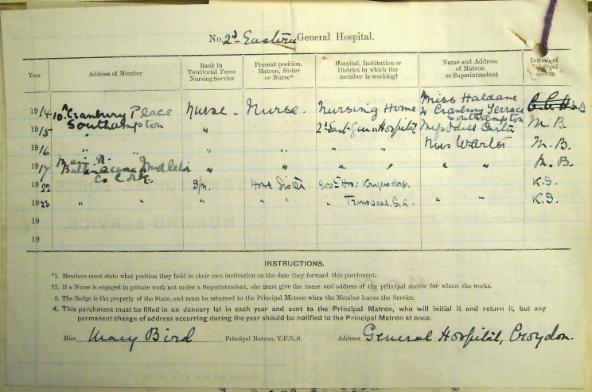

Pre-war, the largest group of trained nurses with some commitment to mobilise with the British military nursing services in the event of hostilities was the Territorial Force Nursing Service. Although under the control of the War Office it was administered in a completely separate way to QAIMNS. From 1909 onwards women enrolled in the service to staff twenty-three Territorial Force General Hospitals planned for the UK in case of war.[48] Those hospitals were ‘virtual’ and although buildings were earmarked, very often schools and colleges, they were an unknown quantity and untried pre-war. In total there was a Territorial nursing reserve of just under 3,000 at the outbreak of war. This number exceeded the requirements for the hospitals but it was recognised that due to work or personal commitments not all members would be available at mobilisation. Although pay and conditions were in most ways identical to those of QAIMNS there were differences in the way the Service was set up. Members were working throughout the United Kingdom and abroad and each nurse had to notify her unit’s Principal Matron of their intention to serve on a yearly basis. Each nurse was provided with a document, Army Form W.4755, usually referred to as a ‘Parchment.’ This contained her name, address and territorial hospital of affiliation and was submitted each year for checking before being returned to her thus ensuring that up to date information was held. Any woman who failed to send in her parchment, or who had reached retirement age or maybe moved abroad on a permanent basis would be removed from the hospital’s roll of nurses. There was never any shortage of eager volunteers waiting to fill a vacancy.

'Parchment' submitted yearly by Margaret Power [The National Archives WO399/13965]

During the early days of August, 1914, we were hourly expecting the word ‘mobilise’ but we had to carry on as though war were a thing remote. The Unit accordingly went to Aldershot for the Annual Camp on the Saturday night of August 1st, and, having pitched tents and made the camp as comfortable as possible on the first day, we went to bed tired out. At 11 p.m. on Sunday a telegram was handed to me ordering our immediate return to London. On Tuesday night, at 11 o'clock, another telegram arrived at Headquarters: ‘Mobilise, act accordingly.’ The first difficulty was that there was nothing to say what the word ‘accordingly’ meant. There had never been a rehearsal, and nothing positive was known as to the source of supply of equipment. Who was to give the order to take over the building and how it was to be done were equally indefinite problems. The only safe course appeared to be to act first and to get authority afterwards.[49]

One of the first things was to gather his own RAMC staff and to make contact with the hospital’s Principal Matron, Ellen Barton. She carried on her own job as Matron of Chelsea Infirmary during the war but also had overall charge of the nursing staff of the territorial hospital. She immediately contacted her members asking them to ‘mobilise’ and so the ball was set rolling. The working Matron of No.3 London General was Edith Holden who wrote much of her experiences during the war in the hospital magazine. She trained as a nurse at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital but at the outbreak of war was working in Dublin and had to make the reverse journey from Reservist Kate Luard:

It was very hot, and I was just starting for a holiday (which I considered I needed very badly) when I was summoned to come to the 3rd London General Hospital. Where that was I didn't know, but I hoped it might be ‘Somewhere in France.’ The taxi, after many wrong turnings, swerved in at a lodge and drew up at a grey-looking building which is now the 3rd London, at Wandsworth. I had often seen that building from the train, but never imagined it would be to me what it now is. I was shown into a long room on the right-hand side of the door, where a few sisters were sitting - waiting, I suppose, to see what I was like. To my relief I knew one or two of them, and we talked of the possibilities of war and our own future outlook on life.[50]

Edith Holden, Matron, No.3 London General Hospital [Gazette of the Third London General Hospital]

The furnishing of the building is very sketchy. In some wards the beds are quite presentable, but in others they are a miscellaneous collection. All was ordered according to the Army Schedule and the result is quite extraordinary. The proper sort of lockers were not specified, and bedside tables were sent. The bottom shelf of the table has to hold all the ordinary kit; no matter how you try, the things fall off. Therefore the wards do not present as beautiful an appearance as we are used to at St. Bartholomew’s.[52]

Ellen Musson was the Principal Matron of No.1 Southern General Hospital, Birmingham, and also found that the buildings taken over at the University fell far short of what she considered suitable:

My first view of the hospital was enough to turn the stoutest heart cold. The ceilings and walls were hanging with smuts, because it was a learning establishment and had not been properly cleaned since it was opened by King Edward. Straw was littered all over the place and, of course, the RAMC people had put the bedding on the floor, of all places! However, I told the CO it would not be possible to get the Sisters to do anything until it was cleaned. I had to report to the Colonel that three of the orderlies were physically unfit, and to their great disgust they had to go back again, and the others set to work to clean the University. The orderlies thought they had made it so clean, but the Sisters set to work and told them they had to do it all over again. They asked me what I wanted, and I said I wanted buckets, and ladders and floor cloths and men.[53]

Within two weeks of the start of the Great War, 4,000 of the nation’s most highly trained professional nurses had moved from their civil positions and been set down with the army. The gap in the establishments of civil hospitals rapidly grew larger as nurses from all parts of the UK and beyond rushed to join the military nursing services. By Christmas 1914 another 2,000 trained nurses had enrolled in QAIMNS Reserve.[54] During that initial period there were fewer enrolments in the TFNS due to the initial staffing method which left a surplus of more than 600 women at mobilisation who could be later employed as needed.[55] As the war progressed there was never a time when military hospitals were fully staffed with trained nurses especially in France and Flanders. It resulted in a constant balancing act between the enormous number needed by the army and the needs of the civil hospitals who lost so much in the way of qualified medical and nursing staff during the Great War.

*****

[36]The National Archives, WO25/3956

[37]The National Archives, service record of Ethel Hope Becher, WO399/501

[38]This was an error in date by Miss Chadwick, as the Saturday was actually August 1st, 1914.

[39]The National Archives, service file of Clara Mavesyn Chadwick, WO399/1411

[40] Service record of Kate Evelyn Luard, TNA WO399/5023; 1911 Census; outline of family history available online

[41]Diary of a Nursing Sister on the Western Front 1914-1915, William Blackwood and Sons, 1915; published anonymously but later publicly attributed to Kate Luard.

[42]No.1 General Hospital, The National Archives, WO95/4074

[43]Entry in Australian Dictionary of Biography

[44] No.2 General Hospital, The National Archives, WO95/4074

[45] The National Archives, WO95/3988, 15/8/14. [DDMS/Deputy Director of Medical Services]

[46]The National Archives, WO329/3253

[47]British Journal of Nursing online, 5 September 1914, page 198 and subsequent editions.

[48] Later in the war increased to twenty-five

[49] The Gazette of the 3rd London General Hospital, Vol.1, No.1, October 1915

[50] Ibid.

[51] The National Archives, WO222/1

[52] St. Bartholomew’s Hospital League of Nurses, League News, January 1915, page 543

[53]St. Bartholomew’s Hospital League of Nurses, League News, March 1916, page 643.

[54]Anne Beadsmore Smith, Matron-in-Chief, QAIMNS, 1920, Army Medical Services Museum

[55]Dame Maud McCarthy, Summing up of the Territorial Force Nursing Service, British Journal of Nursing, 11 December 1920, page 326