THE FAIREST FORCE

10. ACCOMMODATION

*****

The majority of nurses encountered an enormous variety of accommodation during their stay in France and Flanders. If their tour of duty was a long one they were likely to sample most of what was on offer during wartime in the way of tents, huts, hotels, convents, schools and billets. As the war progressed, what had been considered suitable in the early days became outdated and some consideration was given to making conditions more congenial for the long term. Although life was simpler and less materialistic one hundred years ago, most women had not faced active service living conditions before, save perhaps the similarities of two weeks’ summer camping.

When the British Expeditionary Force arrived in France in August 1914 the war was one of movement and to an extent even the base hospitals moved with it. By the end of the month it was found necessary to evacuate the units at Rouen and retreat towards the coast, temporarily opening up at Le Mans, Angers, Nantes and St. Nazaire, and always being prepared to evacuate the country if necessary.[111] By mid-September 1914 the hospitals were returning to Rouen and the Matron-in-Chief settled into office accommodation at Abbeville where she was to stay for the next three and a half years.

A little further along the coast to the north, the British General Hospitals had taken up positions at Havre, Boulogne and Wimereux which most of them would retain until their final closure in 1919 and 1920. Many of the coastal hospitals were sited in existing buildings, particularly hotels, and staff accommodated within them or in nearby annexes, often taking over attic rooms which would have been home to hotel staff in peacetime.

No.3 General Hospital, Le Treport - nurses were comfortably housed here in 'hotel' rooms

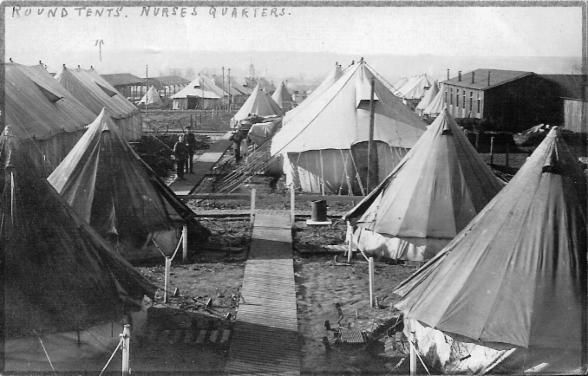

… the Army Commander had complained that the nursing sisters at Contay – 49 and 9 C.C.S. – were under canvas, and he asked me if I would kindly let him have a report on the subject. He said that the huts were under order and also asked if he were right in saying that all sisters were provided with gum boots and Beatrice stoves. I replied that all over France a certain number of sisters were in tents, that nursing sisters for the Armies were specially selected amongst the strongest and most adaptable, that they were always impressed with the importance of being suitably clad and well supplied with things under as well as over their camp beds, that it was always pointed out to them it was probably they might have to live under canvas until other accommodation was provided and that I had constantly come across sisters who preferred living in tents to huts or billets.[112]

Bell tents for nurses' accommodation within a tented and hutted camp

However, around the same time, Miss McCarthy acted swiftly to have nurses re-housed and tents removed after a complaint by the family of a VAD about her living conditions at No.11 Stationary Hospital, Rouen:

I went into the question of accommodation here, where the complaint had emanated from a V.A.D., and found that these girls were still in 2 small marquees, 4 in each, and 2 in a single bell tent – everything of a most unsatisfactory nature. I expressed surprise that after the complaint had been made, some steps had not been taken to improve matters. The bell tents were leaking and sitting in a pool of water just on the edge of a large clay pit. I saw the C.O. and asked him to see that the 2 sisters in bell tents should at once be accommodated in the Matron’s room and sitting room, and the tent be removed.[113]

There is no mention here of the fate of the Matron! Olive Dent, working at No.9 General Hospital provides a compact account of the changes which occurred at her hospital, also situated on the race-course at Rouen:

In the early days some of our nursing sisters had improvised bedrooms from the loose boxes which were near us, in virtue of us being on a race-course. Later, when tents and huts materialised at a quicker rate, these were left for the accommodation of the batmen. Bell tents and marquees were always very popular, being absolutely delightful in summer and very cosy in winter with the aid of stoves. Some nurses who had thoroughly enjoyed life in a marquee during the winter of 1915-1916 were in a rebellious mood at having to go into a hut for some weeks during the winter of 1916-1917.[114]

Where there was no alternative provided, heating in nurses’ accommodation was provided by oil stoves, most commonly the small Beatrice stove which each woman took with her on overseas service as part of her camp kit. In addition to providing some warmth, they were also used to boil water for drinks during off-duty time and women were allowed to draw up to one pint of oil a day to keep their stoves active and themselves warm.

Beatrice Oil Stove

As the war progressed huts soon became a common sight at many base hospitals and also in casualty clearing stations. If a unit vacated a CCS another would soon take its place and existing huts could save a great deal of trouble in the taking down and re-erection of marquees. In some locations huts were taken over on sites previously used by the French, which meant an even wider variety were soon in use.[115]

A French Adrian hut at a casualty clearing station

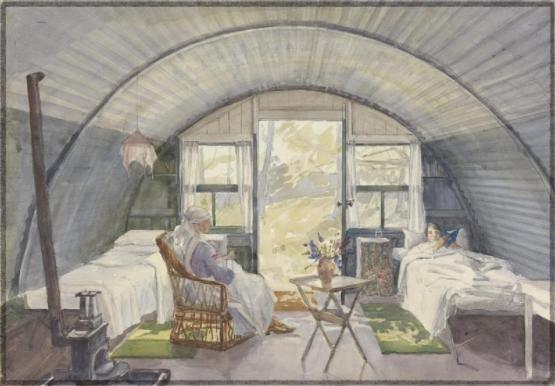

In addition to being used for offices, stores, operating theatres and hospital wards, they also provided accommodation for most of the staff. Nurses were allocated a more generous amount of space per person than the rank and file of the Royal Army Medical Corps and huts were divided into cubicles for either one or two nursing staff according to their seniority. From the autumn of 1916 a small version of the new Nissen hut was used in several locations, each one providing accommodation for four nurses.

Interior of an accommodation Nissen hut at Dieppe by Beatrice Lithiby [IWM ART2895]

All the furniture was of the packing-box variety … chest of ‘drawers,’ whose characteristic was that they did not draw, were built from small boxes on the cumulative principle and by the system of dovetailing. Then a chintz curtain was hung in front. Another chintz curtain served as a wardrobe. Indeed, chintz like charity covered a multitude of sins, the greatest of these being untidiness. In post-war days … the land will abound with men skilled in the art of dug-out furniture, and maidens nimble at throwing together O.A.S. furniture.[116] [117]

And on an inspection of No.9 General Hospital, Miss McCarthy could only add official approval of this description:

All quarters most comfortable, some of the bedrooms exceedingly pretty – only furniture Camp Kit and Red Cross boxes covered with pretty cretonnes, and dados on the wall made with coloured paper of different colours and shades, upon which have been pasted pictures of different kinds.[118]

Casualty Clearing Stations and other units sited in Army areas rather than on the Lines of Communication were usually highly mobile, some moving frequently as the battle area shifted in order to provide immediate and adequate medical care for soldiers. Nurses were frequently billeted out with French families who provided them with board and meals. In May 1917 Kate Luard arrived at her Casualty Clearing Station to find her billet:

… a neat row of little separate cottages in tiny gardens, quite poky but very clean, and kind people anxious to make one comfortable. I had to come to terms with another one who is to faire our cuisine; and she had a nice supper of eggs, coffee and lovely bread and butter for us at 7.30. They have never seen a female Anglaise in uniform before and we caused a terrific sensation; if we stand still a moment the children collect round us and the women rush to their doors and windows.[119]

With so many women from different social backgrounds and with a variety of life experience, there could have been few things that were universally liked or disliked. For every one who enjoyed tent life another must have preferred a cubicle in a hut or an attic room in a hotel. Within the constraints of wartime conditions overseas, the Matron-in-Chief was careful to do her best to provide accommodation that was clean, comfortable and warm and deal with any genuine problems that arose.

*****

[111] For a summary of these movements, see The War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3988 for the months of August, September and October.

[112] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 31 October 1916

[113] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 26 November 1916

[114] Olive Dent, A VAD in France, page 38

[115] An Adrian hut at a casualty clearing station

[116] On Active Service

[117] Olive Dent, A VAD in France, page 38-9

[118] War Diary of The Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 6 January 1916

[119] Unknown Warriors, Kate Luard, Chatton & Windus, 1930, pages 53-54