THE FAIREST FORCE

8. A FOOT IN FRANCE

*****

Nurses disembark at Boulogne [IWM Q7974]

More than 22,000 trained nurses served with QAIMNS and the TFNS during the Great War and over 70,000 nursing members of Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) both in the United Kingdom and overseas. As in any large work force there was a great range of types and dispositions among them, the adventurous, the cautious, the timid, the fearless. All the trained staff had experienced at least three years of hard work during their hospital training often in Spartan conditions but still emerged with a portion of their original identity intact.

In the early months of the war ‘overseas’ was synonymous with ‘France,’ and as the war and the hospitals spread worldwide it continued to be the most desired destination for the majority of nurses. Whilst some women were content to remain in the United Kingdom and care for patients in home hospitals, many were eager and impatient to go on active service. To get to France or some other theatre of war was to be nearer the action, closer to where one’s loved ones might be fighting and suffering and was perhaps seen by some as contributing more to the war effort than the work done by those who remained at home. Members of QAIMNS who were already serving in August 1914 and some members of the QAIMNS Reserve and the Civil Hospital Reserve were quickly despatched to France within days of mobilisation to staff hospitals being set up there to meet an unknown need.

During most of the subsequent four years, nurses, both trained and untrained, were required to prove their capabilities in a ‘Home’ hospital for some months before being considered for overseas service. This system was intended to weed out those whose practical skills or physical frailty might be found wanting in the harsh, pressured environment of active service. However, by 1916 the magnitude of the hospital system and the extreme shortage of nursing staff supported the old adage that beggars couldn’t always be choosers. Nurses previously considered unsuitable for the military nursing services in peacetime were soon found to be essential in wartime.

Before the Great War members of QAIMNS accepted that service abroad, often for several years at a time, was a normal part of their army career but wartime changed the whole nature of the military nursing services. Nurses could express a desire to work abroad but had little control over where they would be posted and to refuse an opportunity that fell short of expectations might result in spending the entire war in the United Kingdom. Military hospitals kept lists of women suitable and willing for overseas service and their chance came when their name reached the top of that list. A full nurse training and many years’ experience was no guarantee that a place would be found for them.

Women who had previously had their tonsils removed were not considered fit for service in Egypt, Mesopotamia or other hot climates, and to look ‘delicate’ was likely to blight any chance of going abroad. On joining the Territorial Force Nursing Service in October 1914, Katherine Daniel’s doctor issued a medical certificate which stated, ‘Her physical condition though showing no organic disease does not warrant her being exposed to the hardships of active service,’ a statement which, despite her pleas, condemned her to ‘home service’ for the next three and a half years. Eventually, after a long period of service virtually untouched by illness, a final appeal from her Matron to the War Office resulted in her wish being granted in April 1918 and she served in France until her final demobilisation one year later.[84]

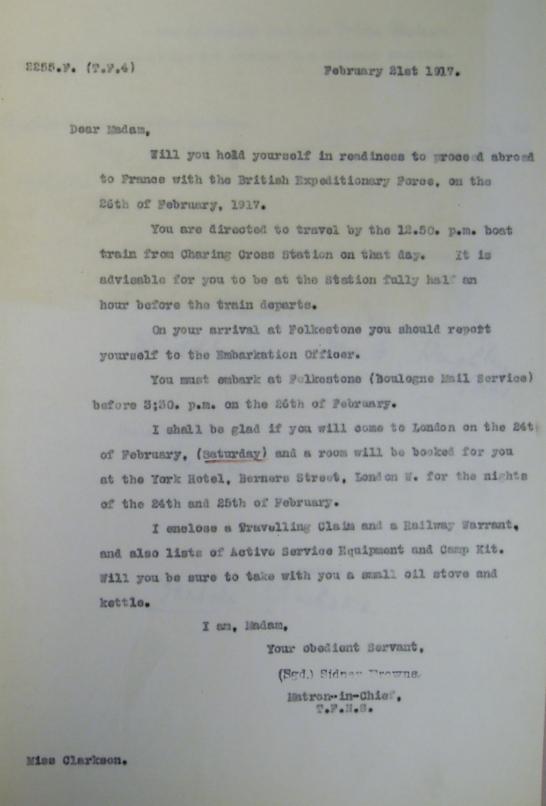

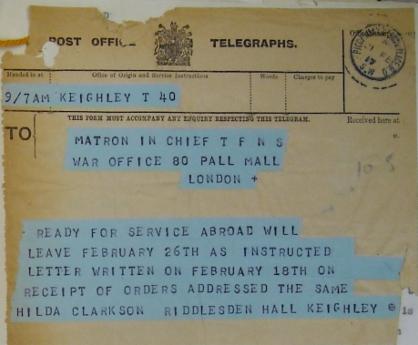

If the wait for a call to proceed ‘on active service’ could take a while, when it came the period of notice was often short and the rush to prepare frantic. Camp kit and additional uniform had to be obtained, though passports were not required if travelling under the authority of the War Office. Travelling arrangements and instructions were sent by letter, or sometimes by telegram for those living or working in Ireland, the Scottish islands, and other more remote areas of the United Kingdom. A first class warrant for railway travel to the port of departure was included and also an embarkation permit without which boarding a cross-channel steamer was impossible. Brassards and identity discs were usually issued from the UK hospital at which the nurse was employed immediately before proceeding overseas.[85]

For travel to France nurses gathered at either Victoria or Charing Cross stations to board the morning boat-train to Folkestone with instructions to arrive ‘fully half an hour before the train departs.’ On arrival at Folkestone they reported to the Port Embarkation Officer who checked their permits before allowing them to board the boat.[86] Nurses might set out from their home or hospital as single travellers but it was unlikely that they would be alone for long, and being in uniform ensured that they soon joined up with other nurses also en route for France. New found travelling companions might not be the first choice for permanent friendships but it was reassuring to have colleagues alongside when undertaking such a momentous journey, often the first time a woman had left the country. Although the cross-channel route from Southampton to Le Havre was used throughout the war for nurses working in hospitals there and proceeding on leave, after the first few months Folkestone-Boulogne was the journey of choice for all ‘first-timers’ travelling to France.[87] For those embarking in Southampton, similar arrangements were made for them on boat-trains leaving from Waterloo Station.

VAD Hilda Clarkson's orders to proceed overseas [The National Archives, WO399/10428]

Hilda Clarkson's reply to the War Office - ready to go! [88: The National Archives, WO399/10428]

Luckily the school washhouse has quite good basins and taps, and we are all camping out, three in a room, to sleep on the floor, as our camp kit isn’t available. No one knows if we shall be here one night, or a week, or for ever!

And more than a week later she was still there struggling with the same conditions:

My mattress, on the floor along the very low large window, with two rugs and a cushion, and a holdall for a bolster, is as comfortable as any bed, and you don’t miss sheets after a day or two. There is one bathroom for 120 or more people, but I get a cold bath every morning early ... we are still away from our boxes, and have a change of some clothes and not others. I have to wash my vest overnight when I want a clean one ...[89]

Within just a few weeks the war became a static waiting game and many British military hospitals were established in positions along the coast which most retained throughout the next four years. Proper arrangements for the reception of nurses were put in place and an experienced QAIMNS nursing sister, the ‘Embarkation Sister,’ placed in charge of ensuring that every nurse arriving in Boulogne was met, accommodated and seen safely onward to her final destination. Her duties were clearly outlined:

i. To meet them at the boat

ii. To arrange for their accommodation and Messing at the Hotel

iii. To arrange transport to units, to the Hotel, and on the following day to the different stations.

iv. To have all kit sorted for the different parties.

v. To notify the Matron-in-Chief of all arrivals as soon as possible, and in accordance with her instructions to detail the prescribed numbers to units stated.

vi. To obtain movements orders and ‘Ordres de Transport’

vii. To obtain all particulars of previous service, etc. from each member

viii. To notify all areas by wire of the members arriving and the day of their arrival.

ix. To prepare detailed Nominal Rolls, and forward them as soon as possible to the Matron-in-Chief’s Office.

x. To check all irregularities in uniform.

xi. To assist in every way possible, all new members arriving.[90]

Believing the army to be all-encompassing, nurses frequently arrived in France without money, and hotel bills were settled for them and advances of pay arranged if necessary. The Territorial Force Nursing Service was well organised in this respect, each member being issued with an advance of one month’s pay and three months’ Field Allowance before embarking, ensuring that they were fully equipped to cope with whatever life had in store. The Embarkation Sister in Boulogne was in no doubt about their credentials:

The organization of the TFNS is sublime, I get a batch of Sisters out; I look at them; and if they are Territorials I heave a sigh of relief. I know that their uniform is correct, their papers are in order, they have enough money, and they know what to do.[91]

After disembarking in Boulogne new arrivals were taken to the Hotel du Louvre which was used as a temporary stopping-place for officers arriving in France.

At times it was late at night before anyone could be found who would undertake to take the luggage of the Sisters from the Quai at Boulogne to the Louvre Hotel, where those passing through were usually accommodated. When possible, the Commanding Officer and Matron of No.13 Stationary Hospital, which was on the Quai itself, would lend a certain number of orderlies to assist in lifting the luggage. At other times French porters were made use of.[92]

Nurses at No.13 Stationary Hospital, Boulogne, 1914 [courtesy of Sheila Brownlee/Ruby Cockburn]

For new arrivals, no definite posting was given prior to landing, at which point vacancies were checked together with each woman’s seniority and experience before allocating hospitals in the most appropriate manner. Some needed only a short ride in a local ambulance or car to one of the many medical units in Boulogne or Wimereux, while others required an overnight stay or longer, before being provided with travel permits and undertaking a lengthy journey by rail to their final destination. The Hotel du Louvre was often the first indication that life in France was of a type previously unimagined:

As we went downstairs a small crowd of other V.A.D.s were standing round a bedroom door shrieking with laughter. They invited us to come along to ‘their room’ and then we laughed too. The room looked like a picture after Hogarth. It contained five beds, three of them fat, French, wooden beds, two of them little iron ones, and it had lately been vacated, or rather was about to be vacated, by some officers. The bed-clothes were lying about in piled heaps, there was a kilt, a Sam Browne, a couple of revolvers, a tin of tobacco, some cigarettes, haversacks and spurs and, tied to one of the bed posts, a huge hound ... An Active-service bedroom, evidently.[93]

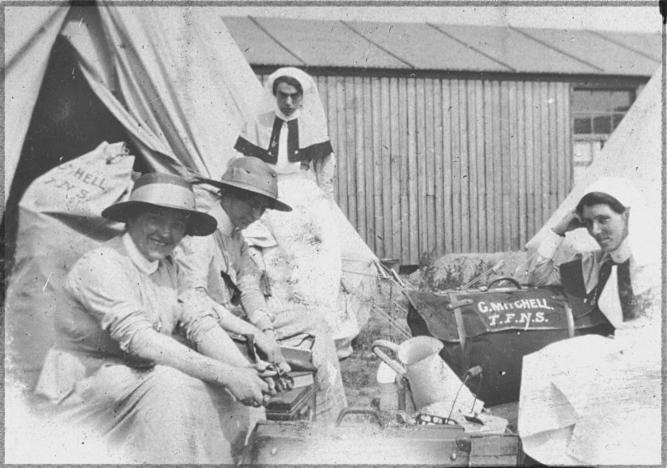

The amount of kit and personal belongings which accompanied each woman was great. She was going to another country to live for an unknown period of time and like a tortoise she had to carry her life on her back. Apart from her uniform which in its most basic form included five dresses, eight aprons, two capes, two cloaks, one hat or bonnet, six collars, six caps and six pairs of cuffs, she needed additional outdoor uniform, both winter and summer underwear, nightwear and at least two pairs of serviceable shoes.[94] Added to this were items deemed necessary for active service abroad. This list, laid down in army regulations, remained virtually unchanged throughout the duration of the war.[95] An allowance of £24.15s was sent to members before embarking for overseas service to cover the cost of both ‘Camp Kit’ and ‘Active Service Equipment.’[96] Camp kit could be purchased complete from military suppliers and supplemented where necessary by a woman’s personal belongings.

1 Trunk not to exceed 30 x 24 x 12 inches

1 Hold-all

1 Cushion with washing covers.

1 Rug

1 Pair gum boots

1 Small candle lantern

1 Small oil-stove and kettle

1 Flat-iron

1 Looking glass

1 Roll-up, containing knife, fork, dessert-spoon, and teaspoon

1 Cup and saucer

1 Tea-pot or infuser

1 Securem tent strap

2 Pairs scissors

2 Pairs forceps

2 Clinical thermometers

1 Portable camp bedstead

1 Bag for ditto

1 Pillow

1 Waterproof sheet, 7ft. by 4ft. 6in.

1 Tripod washstand with proofed basin, bag, and bath

1 Folding chair

1 Waterproof bucket

1 Valise or kit bag with owner’s name painted upon it

Excluding hand luggage, this represented three bulky items for each traveller and considerable difficulties could arise in respect of storage, transport and possible losses.

Early in 1915, the Proprietors of the Louvre Hotel had converted the large garage into a lounge, so that the luggage could no longer be stored there. The Embarkation Sister obtained from the French Customs Officials the permission to use a hut at the very extreme edge of the landing quai, and the luggage was stored there, and later in a room at the Custom House. These officials were most courteous and helpful, as were also those of the Central Station who on one occasion, when there were 129 pieces of baggage, and not sufficient storage room, at very short notice, shunted a wagon into the station in which the luggage was safely stored for the night.[97]

TFNS Nursing Sister Grace Mitchell newly arrived in France with her active service equipment and luggage [Courtesy of Judy Burge and her grandmother Isobel Wace]

As regards the transport from the Hotel to the Stations, the Hotel handcart was used to convey it to the Gare Centrale, and cabs conveyed the Sisters and luggage to the Tintilleries Station.[98]

Hospitals were notified of the approximate time of arrival of new members of staff and transport from the nearest station to the hospital arranged. It was a source of some annoyance to the Officers Commanding medical units that transport frequently returned empty from stations when trains had been delayed or personnel sent elsewhere at short notice without the hospital being informed.

So with a foot now in France a new life of unknown challenges began.

*****

[84] The National Archives, WO399/10741[85] Army Council Instruction 985 of 1915

[86] Information concerning travel from the UK has been difficult to find and these details have been compiled from small items found in the service records of many different nurses, The National Archives, WO399, and in the war diary of the Matron-in-Chief, France and Flanders

[87] WO222 Matron-in-Chief accounts, ‘Embarkation’

[88] Service record of Hilda Clarkson, The National Archives, WO399/10428

[89] Diary of a Nursing Sister on the Western Front

[90] The National Archives, WO222/2134, ‘Embarkation.’

[91] Papers and diaries of Alice Slythe, Liddle Collection, LIDDLE/WW1/WO/107

[92] The National Archives, WO222/2134, ‘Embarkation.’

[93] A VAD in France, Olive Dent

[94] Regulations for Admission to the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service; H.M.S.O., 1916

[95] Standing Orders for the Territorial Force Nursing Service, 1912, Appendix C

[96] Details taken from a selection of service records, The National Archives, WO399

[97] The National Archives, WO222/2134, ‘Embarkation.’

[98] Ibid.