THE FAIREST FORCE

20. AFTERWARDS

*****

When the Armistice was signed on November 11th 1918, the job of the medical and nursing staff in France and Flanders was far from over. For some time there was no apparent change in hospital life except for an absence of large convoys of battle casualties. As the British Army of Occupation moved forward into Germany both hospitals and casualty clearing stations moved with them. The Matron-in-Chief continued to carry out regular inspections and reviews of the accommodation and staffing of these units and she undertook increasingly long journeys over difficult terrain, often needing to be absent from her office for several days at a time. In early March 1919 she spent six days inspecting units newly opened in Duren, Cologne, Bonn and Euskirchen. After the devastation encountered in France, the German towns and cities provided fine accommodation for the patients and living conditions for the staff, though obtaining supplies to supplement rations was a great difficulty in some areas. The reports that are left provide an interesting insight into the British medical services during a period that is rarely written about and little known.

Went with Miss Tunley, Principal Matron, to Bonn. First visited No.21 CCS with staff of 11. The Unit is established in a very fine Hospital, which has only recently been opened, and it will be excellent. There is central heating, very good light and water supply, ample lavatory and bathroom accommodation, and is able to accommodate both officers and men. The nursing staff is accommodated in a wing of the Hospital in beautiful, big rooms, well furnished and with every convenience, and also in a lovely house immediately opposite, with a very comfortable sitting-room, and in addition a grand piano ...

... We then went to 29 CCS. This is a magnificent establishment, situated in a huge park. There are two buildings, one of which is set apart for the men, and the other, a great big red-brick, five-storied house for officers, and the Medical Officers and nursing staff to be accommodated on two different floors. The building for the men was solid, it had only recently opened up, and seemed very comfortable, but the cooking, I should think, was very bad. The other building set apart for officers was evidently before the war, a big private Hospital. There was a long, well lighted corridor the whole length of the building, and the wards opened off it. There were big rooms, and a beautiful big sitting-room, well furnished, and heated, and electric light with plugs everywhere where reading lamps could be attached. I went upstairs to the Sisters’ mess which was equally luxurious and comfortable and where I had a very excellent lunch. I remarked to the Sister in charge that they had apparently the only good cook in the building. She complained of the difficulty in getting supplies, such as butter, eggs, milk, fruit and biscuits, and said that they had to depend entirely on rations ...

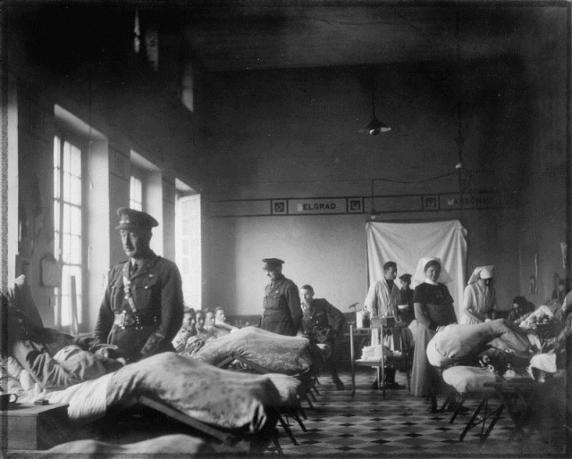

No.22 Casualty Clearing Station, Cambrai, spring 1919 [IWM Q8090]

... I then went to Euskirchen, to No.3 Australian CCS. This Unit is in a magnificent building, with equally fine accommodation both for officers and men, previously a big deaf and dumb Asylum. The Sisters were accommodated in a large house, evidently where the whole of the staff of the Asylum lived before. Solid, well furnished, and with magnificent bathrooms. Here also they were able to get all the extras with regard to food. All these Units which I visited were full of seriously ill people, many of them suffering from Influenza and double pneumonia. They had lost a good many patients, and there were many more who were not going to get better.

Then went back to Cologne to No.36 CCS. Before the war this building was a very big private Hospital, built, furnished, and arranged for the accommodation of paying patients in three grades: 1st class, beautifully furnished bed-room and sitting-room leading off one another and with double doors; 2nd class, smaller well furnished bed-room; 3rd class, wards of various sizes, very comfortable and like our ordinary wards, for the poorer patients who pay as much as they are able to. It was arranged on various floors, but on all there were duty rooms, lavatories and every convenience, and in addition in the little duty rooms, there were places where food could be kept hot, a small oven for hot plates, and a gas ring where three vessels could be cooking at the same time. There was a first rate kitchen and a big laundry, where all the washing of the patients and personnel was done. There were a very large number of patients, many of them critically ill at the time of my visit, and an evacuation was taking place.

Went to No.44 CCS. The Unit is established in an enormous building, ½ of which is devoted to the CCS where 500 can be accommodated, and in the other half German students are working and attending classes in engineering. The Sisters have their sitting room in the building and live in very comfortable flats close to the Unit... Then went to No.64 CCS where I had lunch. This is a great big Hospital and able to accommodate 350... The nursing staff live in a most luxurious house, beautiful rooms, and most lovely china, a very nice sitting room and two floors of bedrooms, the rest being occupied by German people.[257]

No.39 Stationary Hospital, Lille, 1919 [IWM Q8095]

While thousands of women were eager for demobilisation and longed to return to a more stable and permanent life, there was no shortage of those wanting to stay with the military nursing services for as long as possible. With the pressure of war gone, nursing overseas in peacetime was a new adventure. Nurses were not immune from the tragedy of losing loved ones during the war and many wanted a chance to pay their respects to relatives and family members, maybe the only opportunity that would ever come for nurses from the Dominions:

I also spoke to him of the difficulty we were experiencing by some members of the Nursing Services wishing to visit graves, not only of their near relatives, but of distant relations, and in consequence demobilisation was being interfered with. So many of these girls had not even applied officially for permission, and the question of transport was becoming almost impossible. I suggested that with his approval every assistance should be given to members to visit the graves of near relatives, and that the Overseas people should have an opportunity of visiting any graves, whether of near relatives or friends, but that others would have to wait till a later date, as it was not possible to cope with the large numbers wishing to visit graves and have an opportunity of seeing the Front.[258]

In late May 1919, Dame Maud spent four days in London to meet with the heads of various departments, and also for the occasion of her Investiture at St. John’s Gate as a Lady of Grace of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem.[259] She returned to France on the 26th, together with her colleague and counterpart at the War Office, Matron-in-Chief, Dame Ethel Becher. This was Dame Ethel’s first trip to France since before the war and together they spent the following three weeks visiting every part of the country in which British hospitals and casualty clearing stations were still in operation, and also travelled further afield to Germany and Antwerp. Dame Ethel was luckier than many of her more junior staff in managing visits to graves of her friends and acquaintances:

Left Longuenesse 11.30am for Remy Siding, driving through Steenvoorde and Abeele and arriving at No.10 Stationary Hospital at 1pm. Had lunch in the Sisters’ Mess and met the OC, Lt. Colonel Bennett. After visiting the Hospital, went to the cemetery and there was the grave of Captain W. Mellor, 2nd Battalion Royal Irish Regiment, killed on 23.8.14, and 2nd Lt. P. H. Bachelor, 2/8 Warwick Regiment, killed March 1918, who Dame Ethel had known. Left at 2.30pm for Ypres where Dame Ethel was anxious to find a grave of a particular friend. Arrived at Ypres at 3.30pm and after some difficulty found the Graves Registration Hut in midst of many ruins. Met a most obliging Corporal belonging to the office – Corporal Jack Poole, GRU No.3, Ypres, Belgium – who offered to go with us to the cemetery at Weitze, near Ypres, where No.2 Oxford Cemetery is. He took us straight there and fortunately without difficulty found the grave, which was in order with a solid cross well marked at the head. The Matron-in-Chief took two photographs of the grave, one before and one after planting rose trees and pansies. The Corporal is undertaking to look after the grave.[260]

After five years in France and Flanders, Miss McCarthy finally returned to the United Kingdom in August 1919, her wartime job complete. After a celebratory dinner the evening before, a large crowd were on the quay at Boulogne to say goodbye, the event described in emotional terms by her successor in France, Principal Matron Mildred Bond:

On the afternoon of the 5th Dame Maud left by the afternoon boat for England, I went with the D.M.S. in his car to see her off, and Miss G. Wilton Smith and Miss Barbier, C.H.R., went with her in her own car. There was a large crowd waiting on the Quay when she arrived. Among those present were a Representative from G.O.C., - General Asser being absent from Boulogne; the D.M.S. and his staff, Brigadier General Wilberforce, C.B., C.M.G., the Base Commandant; Colonel Barefoot, D.D.M.S., L. of C.; Colonel Statham, D.D.M.S. Boulogne and Etaples; Colonel Gordon, the A.D.M.S. Calais; and many other officers. Major Liouville, who represented the French Medical Service and Messieur M. Rigaud, Secretary to the Sous-Prefecture who represented the French Civil population, came in place of Messieur M. Buloz who was absent from Boulogne. These two men thanked her on behalf of the Military and Civil Authorities for all the goodness and courtesy they had always received at her hands. The Matrons and the Nursing Staff from all the near Units who could be spared from duty and who were anxious to show a last mark of respect to their retiring chief were present. She shook hands with everyone and was wonderful to the last, in the way she carried through a most difficult and trying farewell. Her Cabin was a perfect bower of most beautiful flowers sent from the staff of the different Hospitals. One of her own staff, Miss Hill, V.A.D., was able to cross with her as she was going home on demobilisation. As the ship moved off the Matron-in-Chief, Miss Hill and Major Tate, R.A.M.C. of the D.M.S. staff, who was proceeding to England on transfer escorted Dame Maud on to the bridge and remained with her. They all waved from the bridge and we all waved and cheered our loudest and sang “For she’s a jolly good fellow” as the ship sailed out of the harbour. I think we shall never forget that sight and shall always like to remember the courageous and plucky way in which our chief carried our flag flying to the very last moment into her civilian life, where we wish her all happiness and success and where she will still command the love and respect of us all.[261]

While the British Army of the Rhine continued to expand, the number of medical units in France and Flanders slowly decreased and the staff demobilised. In November 1919, one year after the Armistice, there were 249 trained nurses and 119 VADs, both nursing and general service, working in France and Flanders.[262] Miss Bond and her staff continued to maintain the war diary as before until the date on which it was no longer required, the last day of March 1920. At that time, fifty-three trained nurses and twenty-one VADs remained to staff the two casualty clearing stations and three hospitals that were still open to serve the 28,000 servicemen and women on duty in the country. Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service marked time during the Great War; any women who left the service were replaced but the many thousands of nurses recruited in wartime were employed on short-term contracts. It was not thought advisable to permanently employ more women in wartime than would be needed afterwards and QAIMNS ended the war in the same position with regard to staff as it had started – with approximately 300 trained nurses in permanent, pensionable posts.[263]

Nursing Staff of No.36 Casualty Clearing Station on the Rhine at Cologne, 1919 [IWM Q7383]

New military hospitals were opening in Germany to serve the needs of staff and families attached to the British Army of the Rhine and it was obvious that Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service must expand to meet that need. From the summer of 1919 recruitment for permanent staff started for the first time in more than five years. Most of the new members of QAIMNS were drawn from the ranks of women who already had proven service during wartime with QAIMNS Reserve or the TFNS. This method ensured that the War Office had a sound pre-existing knowledge of their applicants’ experience and personalities with few doubts as to suitability. Together with younger and less experienced women who had been encouraged to train as nurses during wartime they would become the heart of the new service which grew rapidly in the inter-war years.[264] Although it could not have been foreseen in 1919, many would go on to face war once again twenty years later.

*****

[257] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 2nd to 6th March, 1919

[258] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 23 April 1919

[259] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 24 May 1919

[260] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 28 May 1919

[261] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 5 August 1919 (visits)

[262] War Diary of the Principal Matron in France and Flanders, The National Archives, WO95/3991, Summary dated 1 November 1919

[263] Figures extracted from The National Archives, WO25/3956

[264] Ibid.