THE FAIREST FORCE

14. SICKNESS AND CONVALESCENCE

*****

From the earliest days of war great care and attention was paid to the health and well-being of nurses working in France and Flanders. Any nurse reporting sick was allowed to remain in her own quarters for up to twenty-four hours especially if the complaint was minor, but for anything more serious or needing a longer period of care, private houses and hotels were taken and converted into small hospitals for sick nursing sisters.[154] These units existed in the larger base towns, and wards were also set aside in hospitals where infectious cases were treated. As a general rule, women were allowed a maximum of 21 days’ sick leave in France at any one time and if they were not fit to return to duty at the end of that time they were transferred back to the United Kingdom to continue their treatment and convalescence, their condition being assessed at regular military Medical Boards.

As in other areas of the army, no nurse could be discharged until fully recovered or her disability was deemed permanent by a Board. It’s difficult to satisfactorily assess the general level of illness within the military nursing services in France due to a lack of documentary evidence. From August 1915 the war diary of the Matron-in-Chief gives the number of women sick in the UK at the end of each month, and from February 1917 these figures include the daily number of nurses accommodated in Sick Sisters’ hospitals in France. The numbers vary from day to day and season to season as might be expected but overall they show that somewhere between 5% and 10% of the total nursing establishment in France and Flanders were likely to be sick, or on sick leave, on any particular day.

Nurses suffered from a whole range of illnesses and conditions prevalent in the general population. Diseases such as measles, scarlet fever, influenza and chest infections were common, but also gynaecological problems, skin conditions, appendicitis, rheumatism and more rarely, acute mental illness and fulminating infections such as meningitis. Broken limbs were not uncommon, often resulting from motor and bicycle accidents, and danger from bathing in the sea was ever present.[155] As the war progressed many nurses were sent home suffering from ‘General Debility’ often the result of overwork, lack of free time and recreation, and simmering low grade infections that never fully resolved. In an age when the lack of antibiotics often meant the difference between life and death for a soldier, a septic finger or ear-ache could become so severe that it could lead to permanent disability for a nurse.

Sick Sisters’ Hospitals were designed to provide a pleasant and relaxing atmosphere for their patients and considerable care was taken with furnishings and colour-schemes. When some wards at No.5 Stationary Hospital, Abbeville were being converted into accommodation for sick nurses, Miss McCarthy noted in her diary:

Colonel Meadows, S.M.O. Abbeville, called with reference to the conversion of some of the wards of 5 Stationary Hospital for the accommodation of sick sisters. He said there was great difficulty in getting wall paper, which will have to be ordered from Paris, and there was a doubt whether the rooms would be ready by the 15th.[156]

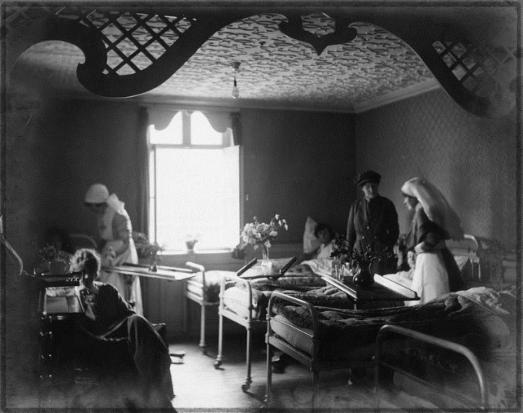

These interiors may look dated and stark by today’s standards, but compared with life in a tent or hut surrounded by mud and cold, they must have provided a welcome change.

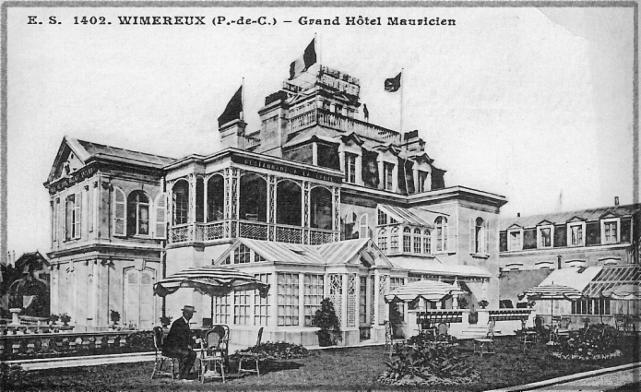

Pre-war photo of the Hotel (Chateau) Mauricien, the exterior of which remained relatively unchanged during wartime

Ward scene inside the Chateau Mauricien, with Nursing Sister, VAD and female Medical Officer [IWM Q8006]

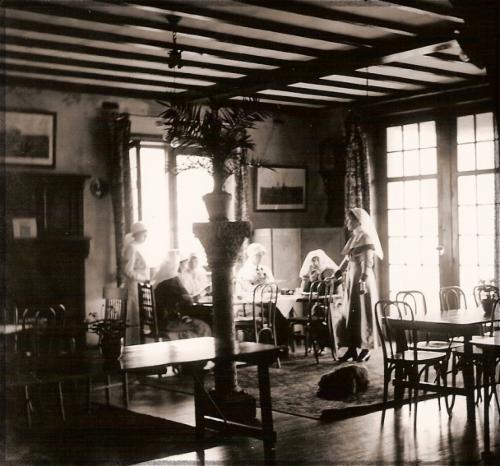

The Chateau Mauricien at Wimereux retained some of the pre-war grandeur it had displayed as a well patronised hotel, while the Villa Tino which covered the Etaples area was a large chateau formerly owned by a Serbian Count and set in the quiet forest of Le Touquet. It boasted nine bathrooms, one with a sunken Roman bath complete with mosaics, but this must have been thought far too fanciful for nurses in wartime and it was covered and converted into the operating theatre.[157] The medical and nursing staff for these units were drawn from local military hospitals and the most eminent consulting physicians and surgeons called upon to advise on more complicated aspects of care.

Dining Room at the Villa Tino, Le Touquet, Sick Sisters' Hospital for the Etaples Area [IWM Q8032]

Many nurses employed in base towns were easily transported to their local Sick Sisters’ Hospital when necessary by car or ambulance, but for those working in units nearer the Front staff sickness could create a great problem both of care and of transport. Although it was not usual for members of the nursing staff to be cared for by their colleagues it was unavoidable on some occasions. As the British army advanced for their final push in early November 1918, the forward medical units became detached from the facilities of the Base towns. As Miss McCarthy travelled further west on her round of inspections she stopped at a Field Ambulance at Pont-à-Marcq, south of Lille:

… where a staff of four had been sent to nurse refugees. They were in a small French Hospital, a great many of them had been evacuated, but there were still many more to go. I found that the Sister in charge, Miss Preston, was nursing one of the staff, Miss Toher, who had Pneumonia and who had apparently been kept 2 ½ days off duty before being seen by a Medical Officer. I found that Miss Preston was nursing her day and night, and sleeping in the room. I arranged for her to do day duty and Sister Allison night duty, and the 4th Sister, Miss Grant, to return to No.39 Stationary Hospital next day, as there was a French lady looking after the refugees, who could manage.[158]

On December 4th, 1918, Miss McCarthy visited No.23 Casualty Clearing Station at Auberchicourt, and found:

Another large Unit in many scattered buildings in the town, the Nursing Staff being accommodated in a row of little villas, one of which had been set apart for the care of 2 Canadian Sisters who had been on the “Dangerously Ill” List, and where they had ‘Specials’ on day and night duty. Miss Harrison was convalescent and would soon be sent to the Base, Miss Tate was still in a very serious condition, her Sister, a Canadian Nursing Sister, and her brother, both there. Her temperature had continued high for 13 days, and in addition to her chest complications, she had some Nephritis, and consequently the Medical Officer was not quite satisfied with her condition. This Hospital also was very full of patients, and one and all complained of the great difficulty of evacuating the patients: up to the present the only way had been by sending them by Ambulance long distances to the next C.C.S. where they were taken in and then again evacuated by road to another Station before they were able to get to a railway siding.[159]

The double pressure of caring both for patients and their colleagues must have caused great concern, but the long experience of all the trained staff in these units undoubtedly resulted in the very best care being given under difficult circumstances.

After a spell in a Sick Sisters’ Hospital most women were fit enough to return direct to duty. For those still requiring a short period of convalescence, houses were opened where nurses who were no longer in need of medical care could relax and recuperate. Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, offered her villa in the forest at Hardelot, convenient for many of the base hospitals, and other facilities opened at Le Touquet, Cannes, Le Tréport and Etretat. A full account of these facilities can be found on the Scarletfinders website as part of a series of reports written by the Matron-in-Chief.[160]

If complete recovery seemed unlikely in the short term, women were assessed by a medical officer who could authorise their evacuation to the United Kingdom, either to hospital, or to their own home. As with sick soldiers, even if return to the UK was inevitable, a patient would not be moved until her condition was stable enough to cope with the rigours of a long journey. Nursing Sister Christine Cameron went straight to France in August 1914 after being mobilised with the Civil Hospital Reserve. She was a competent and hardworking nurse but while working at No.3 Casualty Clearing Station in May 1917 she was taken ill with an acute kidney infection. This became so severe that she remained on the ‘Seriously Ill’ list at the Sick Sisters’ Hospital in Abbeville for more than two months, needing a ‘special’ nurse both day and night. She was eventually evacuated to the United Kingdom on August 7th, accompanied by her personal nurse, Miss Jolly, who had been with her throughout.[161] From disembarkation she was taken to the Queen Alexandra Military Hospital, Millbank, where she spent a further six weeks before going home to Fort William for three months sick leave. In December 1917 she was found to be permanently unfit and her engagement was terminated a month later. Miss Cameron did make a complete recovery and in October 1918 became one of the very early members of Princess Mary’s Royal Air Force Nursing Service where she served until her retirement in 1928.[162]

Medical Boards convened to examine sick nurses had to decide whether the illness or disability was caused by a woman’s military service. This decision was important as it could affect future rights to a pension. Although surviving papers rarely tell the whole story, outcomes sometimes seem rather personal and subjective on the part of the examining medical officers with similar conditions being treated in different ways. A condition could be deemed ‘in and by,’ ‘in but not by,’ ‘attributable to’ or ‘aggravated by’ military service, each of these categories resulting in different judgements. The cause of Christine Cameron’s illness was deemed ‘in but not by,’ which seems harsh in the light of many similar cases being found ‘in and by’ due to ‘the strain of nursing duties.’ Each woman had to produce a medical certificate prior to her employment with QAIMNS or the TFNS, supplied by her local medical practitioner. Needless to say, those which survive in service records are always favourable, otherwise the nurse would not have been employed. However, they could not always be taken at face value. Ada Catherine Poole was thirty-five years old when she was accepted for the QAIMNS Reserve in September 1918. Two months later she was examined at a Medical Board as by that time she had already had sixteen days sick from her work at Devonport Military Hospital. The Medical Office commented:

Although her duties have been very light since joining she is physically incapable of performing them. She complains that she is not able to walk upstairs and gets attacks of dyspnoea [shortness of breath] at the slightest exertion. She was not examined she states by a Board on entering the service. [162A]

The decision of the Board was that her condition was present prior to her employment, and was in no way attributable to, or aggravated by military service. She was discharged a week later. Her name was still on the General Nursing Council Register in 1942, indicating that she continued to be actively involved in nursing, so in the ensuing years she must have found work to suit her in civil life.

Women being evacuated from France on the Hospital Ship 'St. Andrew,' still in hats and coats! [IWM Q7997]

There are a very small number of women who receive a great deal of publicity in books and other media on account of their death through enemy action while on ‘active service’ in France and Flanders. These few deaths though sudden and particularly distressing formed only a small percentage of the fatalities among the nursing staff in France, the majority of whom died of illness and disease which might have been encountered by anyone within the civilian population. The causes were many and varied; measles, meningitis, pneumonia, cerebral haemorrhage, and acute surgical emergencies such as appendicitis and perforated ulcers. Nurses occasionally suffered from acute mental illness which, on two occasions, was severe enough to result in suicide.

Miss P___ was a nurse of some experience. She was thirty-four years old and trained first as a children’s nurse, later receiving a full general training at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London. In 1912, soon after completing her training, she joined Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, and by the outbreak of war already had considerable experience of army life. In April 1915 while working in Rouen, she was admitted to hospital with a mental illness, variously described as ‘neurasthenia,’ ‘nervous excitement’ and ‘depression.’ Her younger brother had been killed in France five months earlier while serving with the London Rifle Brigade and another brother was on active service which must have caused her constant worry. On the 24th April she was admitted to hospital in Rouen suffering from a ‘nervous breakdown,’ and three days later transferred with a nurse escort to the officers’ section of No.2 General Hospital, Le Havre, prior to evacuation back to the United Kingdom.[163] On the 29th April 1915, the day she was due to depart, she committed suicide by jumping from her third floor hospital room, her cause of death given as ‘Died from injuries sustained by falling from a window.’ At the Court of Inquiry held later the same day, the events that led up to her death were described by the nurses caring for her. Ethel Barber was the Sister-in-Charge of the Officers’ Section at that time:

I noticed that the deceased was suffering from nervous excitement but not to a marked extent and seemed cheerful. She seemed to be worrying more about a fellow patient - a nursing sister who had come down in the same train with her from Rouen - than about herself ... She was never left alone, being always watched very carefully, although she never shewed any signs of a suicidal tendency. On 28th April she became more and more quiet and began to shew signs of depression which were attributed mainly to over fatigue ... I saw her five minutes before she went out of the window and I told her it was time to get dressed ... I walked straight down the stairs and before I reached the bottom I heard the Orderly shouting for the Medical Officer ... I went at once to the pavement and I recognised her as Acting-Sister P___.[164]

And Sister Florence Davis, in charge of her care added:

She was to have gone on board the hospital ship in the course of the morning so I gave her her clothes but she seemed disinclined to leave her bed at first and then I offered to help her dress. She said she would rather dress herself ... I turned to help the other patient ... No sooner had I done so than I turned round and found the deceased at the window which was about four paces from her bed. I made a dash for her but it was too late.[165]

It was a tragic end for an educated, professional woman, and although cases such as this receive little of the publicity attached to the few who died through enemy action, the despair of the family concerned could not even have been alleviated by any perceived ‘glory’ in the manner of her death.

Considering the arduous conditions of active service in France and Flanders, often in cold and damp accommodation and with few periods of leave, most nurses adapted well and found their health unimpaired by the hardships of their life and work. Facilities for sick nurses provided comfortable and caring surroundings and there was a general willingness to transfer women back to the United Kingdom whenever necessary. Details can certainly be found for a number of nurses whose mental or physical health was undermined by their war service, more commonly following postings to hot climates where tropical diseases were prevalent. It’s not possible to accurately assess how many of these women would have suffered similar medical problems if they had continued their pre-war work in civil hospitals or private homes.

The names of 734 nurses discharged on the grounds of illness or disability attributable to war service appear on the Silver War Badge medal roll.[166] However, this cannot be taken as an accurate reflection of the number actually incapacitated during wartime. Of the total number, 432 of the awards were to members of the Territorial Force Nursing Service, and another 162 to members of Voluntary Aid Detachments. This leaves just 140 to QAIMNS and its Reserve, a very low figure taking into consideration that the service actually employed more nurses than the TFNS, both at home and abroad. Although a great deal of work would need to be done to prove the point, it does seem that it was less likely for a nurse attached to QAIMNS Reserve to either claim, or be awarded, a Silver War Badge, thus minimising, on paper, the physical effects of wartime on members of that Service.

Even in civil life during peacetime nursing was an arduous profession. It is probably impossible to estimate the true cost of war on the health and well-being of military nurses who served during the Great War. Emphasis and publicity invariably fall on those who felt they had suffered illness attributable to war service while the rest remain a silent majority.

*****

[154] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3988, 8 July 1915

[155] This is expanded on in section fifteen, ‘Off Duty.’

[156] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, WO95/3989, 11 December 1916

[157] In All Those Lines, the diary of Sister Elsie Tranter 1916-1919, page 45; edited and published J. M. Gillings and J. Richards, 2008; and Diary of Matron-in-Chief, WO95/3988, 3 November 1915

[158] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, WO95/3991, 3 November 1918

[159] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, WO95/3991, 4 December 1918

[160] Scarletfinders: Report on the Convalescent Homes for Nurses in France, 1914-1919; The National Archives, WO222/2134

[161] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 25 July 1917 and WO95/3990, 7 August 1917

[162] Christine Cameron service file, The National Archives, WO399/1264

[162A] The National Archives, WO399/6694, service file of Ada Catherine Poole

[163] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3998

[164] The National Archives, WO399/6558

[165] The National Archives, WO399/6558

[166] The National Archives, WO329/3253