THE FAIREST FORCE

18. LEAVING

*****

Leaving Boulogne in 1919

At the start of the Great War there were less than three hundred military nurses serving under contract to the War Office, all members of the permanent staff of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service.[230] Despite the massive increase in the number of trained nurses employed with QAIMNS Reserve and the Territorial Force Nursing Service for the duration of the war, estimated at about 22,000, the establishment of QAIMNS itself remained static.[231] A handful of women were accepted into the ‘regular’ arm of QAIMNS to replace those women who left, but the authorities were careful not to offer permanent, pensionable contracts which might result in a surplus of staff when peace came. Thus, when hostilities ceased and the numbers of hospitals and casualty clearing stations began to fall, it became increasingly urgent to dispense with the services of nurses, both trained and untrained, as quickly as possible. The enormous national debt that the United Kingdom had accrued as a result of the war had to be trimmed in every way possible.

On the last day of October 1918 the total number of nurses serving with the British Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders amounted to 8,061 women and by August 31st 1919 that figure had dropped to 1,259 covering all grades.[232] Although these figures show that there came a point after the Armistice when it was imperative to get rid of people quickly, for most of the war the nursing establishment in France had been below requirements and the authorities struggled to find enough nurses of the right calibre from within a rapidly diminishing pool. There were on occasions women whose work or behaviour were so poor that it was felt necessary to dismiss them, though this became less frequent during the second half of the war as staff shortages grew more severe and attitudes towards sub-standard behaviour changed.[233]

All women serving as British military nurses signed contracts with the War Office giving an undertaking that they would serve for a certain period of time. In the case of the few permanent members of QAIMNS that agreement included an understanding that resignation in wartime was not allowed, though it is hard to see how it could have been enforced in practice other than by the refusal to supply a testimonial on leaving. There are also frequent references in the war diary of the Matron-in-Chief indicating that members of the Territorial Force Nursing Service were not permitted to resign during wartime, most phrased in a similar manner to this one:

Resignation received Miss I. F. Allen TFNS, returned DMS 1st Army informing him that the TFNS is enrolled for duration of war – resignations only accepted under very exceptional circumstances.[234]

However, service records of members of the service show that a number of different contracts were supplied and while most did use the wording ‘so long as my services are required during the present emergency,’ others were a variation on the QAIMNS Reserve contract with the rather more flexible phrase ‘until the expiration of 12 calendar months, or until my services are no longer required, whichever shall first happen.’ So a blanket ban on resignation for TFNS nursing sisters could never have been the case and although some women might have been persuaded by mild threats to stay, most were under no obligation to do so as long as they had met the conditions of their individual contract.[235]

A proportion of trained nurses serving with the B.E.F. in France signed contracts for twelve months at a time and were free to resign at the end of the period, which many did, particularly those from Canada. Other women signed for an indefinite period ‘as long as my services are required’ and for them it could be a little trickier to leave. In exchange for the more difficult terms of this contract they received an extra amount of £20 a year added to their pay, which for a Staff Nurse increased her basic salary by 50%. Unless forced to leave due to ill-health or some other unsuitability, they were required to pay back part or all of their previous year’s extra allowance on resignation:

Circulated instructions received from War Office regarding those members who sign A.F.W. 3538 or 3548 and are desirous of resigning. A written statement as to their willingness to refund the extra pay drawn is required of them.[236]

Sympathy was invariably shown to nurses suddenly confronted with situations not of their own making which needed immediate action. At the height of the influenza epidemic of late 1918 members of the nursing services were faced, like many others, with previously unimaginable circumstances:

Forwarded and recommended to D.G.M.S. application from Sister M. Richardson, T.F.N.S. to be permitted to resign her appointment owing to the death of her Mother and of her Sister, who has left a baby in delicate health, of which she is to take charge. Sister Richardson states that she is unable to refund the extra pay she has drawn through having signed A.F.W. 3545.[237]

And just two days later the sudden resignation of another woman, also suffering as a result of the war:

Forwarded and recommended to D.G.M.S. application from Mrs. J. F. Milne, V.A.D., Harvard Unit, to be permitted to resign her appointment as her husband is missing. She is anxious now to be in England as she hopes that he may be returned as a prisoner of war.[238]

By the summer of 1916 many nurses were suffering from tiredness and general debility due to the high pressure of work and often inadequate periods of leave, leading to an increased number wishing to resign. In an effort to stem the flow, a new six-month contract was introduced as it was hoped that a shorter commitment would be an inducement to stay. By that time many nurses had been in France for nearly two years and the harsh conditions and apparent lack of opportunity for professional advancement were making their position increasingly unattractive.

Miss Nunn, A/Matron 2 Stationary wrote to say Nurses Jickley, Lock and Lyons were going to resign. Jickley and Lyons because they were still S.N., [Staff Nurse] having been out since August 1914, both Guy’s trained. Miss Lyons has been awarded the ARRC [Royal Red Cross, 2nd Class] and wrote to me direct, saying that she could only suppose that her work must have been considered eminently unsatisfactory by the Army and she had been honoured with a decoration!!!! Miss Lock was resigning because she had only done base work. I shall go to 2 Stationary Hospital on Monday and will then see these discontented ladies. Considerable dissatisfaction exists in consequence of so many young nurses coming out straight from England with stripes,[239] while many who have been here from the beginning are still only doing Staff Nurse’s duties.[240]

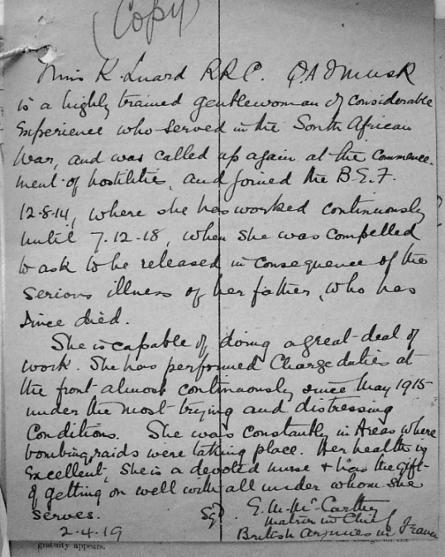

Having made a firm decision to resign either at the end of a defined period of service or due to other personal reasons, one month’s notice was the usual period required. Application was made through the Matron in charge of the hospital at which the woman was employed and then passed through to the office of the Matron-in-Chief. If there were any unusual circumstances, Miss McCarthy was obliged to seek the advice of either the Director of Medical Services of the relevant area, or of her counterpart at the War Office, Ethel Becher. A confidential report on the work and conduct of each individual was forwarded from the hospital to the Director General of Medical Services (D.G.M.S.).[241] Testimonials and references were not issued at the time of leaving but would be sent on request, either to future employers or in some cases to the woman herself. Below is the personal reply sent by Maud McCarthy to Kate Luard in April 1919 in answer to her request for a reference for future employment:

A very personal testimonial from the Matron-in-Chief to Kate Luard [The National Archives WO399/5023]

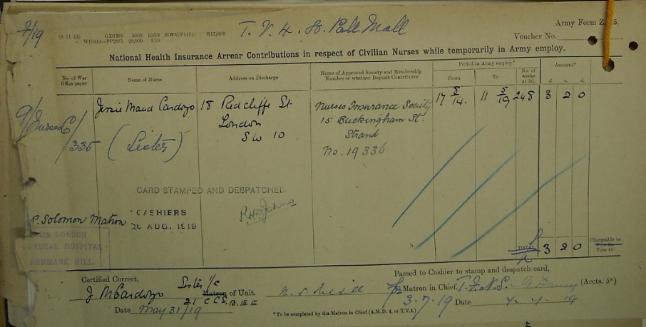

With the confidential report went the form for service gratuity to be claimed, and details of the society, if any, with which she was insured prior to her military service. The War Office paid the 3d required of employers for every week of military service to ensure there were no gaps in insurance cover for health or sickness. If a woman was not insured immediately before she entered army service, then no contributions were paid by the army nor any refunded on leaving to cover the period of war service.[242] The form Z.25 below for Jessie Cardozo shows that before the war she was insured with the Nurses’ Insurance Society in London, one of the largest nationally.

Insurance arrears form Z.25 for Jessie Cardozo [The National Archives, WO399/10275]

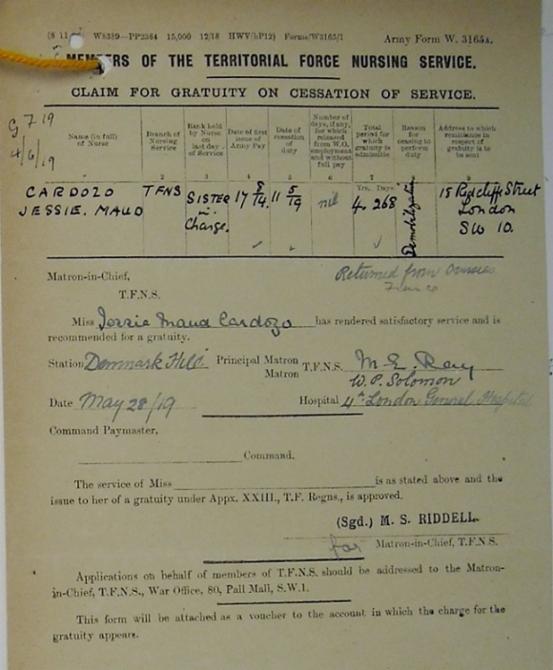

Gratuity claim form W.3165 for Jessie Cardozo - these are always useful for giving the exact length of service in years and days

[The National Archives WO399/10275]

At the end of the period of notice, permission for embarkation was issued and arrangements made for overnight accommodation in Boulogne if it was necessary to break a long journey. A first-class travel warrant covered the journey from arrival in Folkestone to the home railway station. Women would usually be asked to notify the War Office in writing of their arrival in the United Kingdom or to present themselves at the War Office if the circumstances surrounding their resignation were unusual or needed further investigation. Uniform counted as personal property and could be kept, destroyed or passed on to colleagues, and as the war progressed the recycling of uniform proved an important economy.

Whatever the reason for resignation, opportunities for nurses to find employment in civilian life were abundant in wartime, in hospitals, private homes, industry and in a community setting. However, some nurses found themselves drawn back by the war and either re-engaged with the British military nursing services or joined one of the many other organisations such as the British Red Cross, French Flag Nursing Corps or Scottish Women’s Hospital which employed trained nurses in their hospitals both at home and abroad. For the trained nurse, the Great War was a time of occupational abundance, offering many and varied opportunities to travel and gain further experience, both professional and personal.

*****

[230] See section one ‘Before the War.’

[231] Figure based on the number of surviving WW1 service records held at The National Archives, and estimated number of records either destroyed between the wars or still retained by the Ministry of Defence

[232] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, see summary of staff at end of each month’s entries

[233] An example of the changing attitude of the Matron-in-Chief is outlined in section seventeen, ‘Discipline’

[234] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 24 July 1916

[235] Also see section five, ‘Contracts’

[236] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3990, 21 December 1917 and Army Council Instruction 522 of 14th May 1918

[237] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 20 November 1918

[238] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 22 November 1918

[239] ‘Stripes’ refers to Nursing Sisters being allowed to wear two scarlet stripes on the forearms of their working dress to indicate their higher rank

[240] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 10 June 1916

[241] See section seventeen, ‘Discipline’

[242] Examples of these forms can be found in almost every service file, The National Archives, WO399