THE FAIREST FORCE

19. DEMOBILISATION

*****

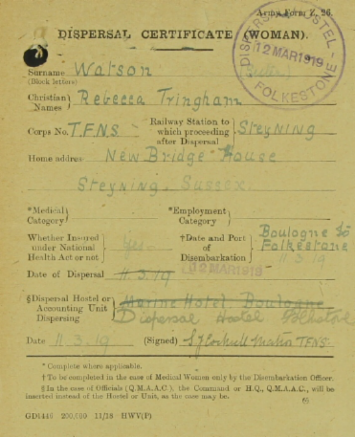

Demobilised VADs and other women workers leaving Boulogne 1919 [IWM Q7999]

Demobilised VADs and other women workers leaving Boulogne 1919 [IWM Q7999]

After the Armistice, the regulations relating to demobilisation were rather different from those covering resignation during wartime, and although nurses could still request to leave, many simply waited their turn for the inevitable axe to fall. As soon as the military situation had settled it was obvious that the need for medical facilities would be reduced. With so many personnel still in France and Flanders and the Army of Occupation taking up positions in Germany, there remained a long-term continuing need for nursing staff but on a different footing from before. From November 1918 nurses soon realised that their jobs would not be secure for long and many began to look for new posts or make arrangements to return to former employment which had been kept open for them.

[Full details of the demobilisation process covering all grades of staff can be found in ‘Demobilization Regulations, 1914-1918,' The National Archives, WO33/3398, paras. 312-3 and 1327-1336].

By the early spring of 1919 the War Office was urging Miss McCarthy to push on with rapid demobilisation and facilities were opened in Boulogne, Folkestone, and at Balmer Lawn, Brockenhurst, to be used as transit stations and dispersal hostels. Some nurses were eager to put the war behind them and start afresh while others clung desperately to their military roles. Previous rules about nurses having to repay part of their salary if leaving prior to the end of their contract were set aside as the needs of the Army took priority.

Received War Office letter stating that there was no objection to V.A.D. resignations being accepted, and pointing out that if applications for V.A.D. Members to be allowed to resign and break their contracts were forwarded and recommended for favourable consideration, it is assumed they can be spared, and in this case reliefs will not be sent.[243]

From the beginning of 1919 the War Office pushed relentlessly to get demobilisation moving as quickly as possible, and Miss McCarthy found the inaccuracies in their figures and the perceived lack of understanding of the position with regard to staffing, frustrating:

Sent memo to D.G.M.S. pointing out discrepancies in War Office wire of 9th with regard to release of nursing staff. War Office wire gives strength of nursing services, all ranks, on January 30th as 3971. Our returns shew number of Nursing Staff on February 1st as 6099. War Office wire gives strength of Nursing Services, all ranks, on November 11th as 4158, our returns shew strength as 7273. Thus from this Office records it will be seen that 1174 nurses have been demobilised from France on February 1st, and by March 9th, this number had been brought up to 2475. Also War Office wire states that ‘at least 400 nurses must be demobilised every week until establishment of nursing personnel had been reduced by ½’, and it is pointed out that on February 1st total number in country was 6099, and on March 9th, total was 4798. These numbers are being further rapidly decreased, and under present conditions it is thought that the numbers of nursing staff in B.E.F. should not be reduced to minimum strength until establishment of Army of Occupation, as well as rest of L. of C. and other Armies, is settled.[244]

Many employers applied to the War Office to have staff released to resume their civil posts and those requests were treated as a priority.[245] Nurses wishing to be released urgently, produced a multitude of reasons though not usually that stated by Acting Sister Blamire Brown who decided that ‘hostilities have now ceased and she no longer feels that it is her duty to continue serving’.[246] Numerous requests were being received daily at Abbeville, and a single day in January 1919 saw a wide range of different reasons given:

Forwarded to D.G.M.S. for consideration application from S/Nurse P. Pritchard, Q.A.I.M.N.S.R., to resign on termination of contract 26.3.19 as she is anxious to return to Canada.

… application from A/Sister M. R. Ashford, Q.A.I.M.N.S.R. to resign her appointment on termination of contract on 15.2.19, as she is needed at Home to relieve her Sister who is anxious to commence her training.

… application from S/Nurse L. Tonge, Q.A.I.M.N.S.R. to resign her appointment on February 13th, as she is going to be married to an Australian, who embarks for Australia early next month.

… application from S/Nurse M. Foster, Q.A.I.M.N.S.R., to be released from her contract in order that she may return to a post which is being kept open for her in the Transvaal.

… application from Miss G. S. Chrystie, V.A.D. to terminate her contract which expires 13.6.19 on account of being needed at Home, as her Sister is being married and her Father is a widower.

… application from Miss C. Parker, Special Probationer, to be released from Army Service as she is required at Home.

… application from Miss H. M. Bullogh, V.A.D. to resign as her Sister is being married, and her Mother will be left alone.

… application from Miss O. Mitchell, V.A.D. to resign her appointment owing to the grave state of her father’s health who is 84 years old.

… application from Miss M. M. Auchinlech, V.A.D. to resign in order to be married, as her fiancé has been demobilised and is going to South America.[247]

The photo may have faded but the joys of going home are still obvious ninety-five years later

It soon became obvious that where a War Office contract stated ‘as long as my services are required,’ it meant exactly that, and the demobilisation process could be condensed into a period as short as forty-eight hours. There were bitter complaints in some quarters about the process of demobilisation and the problem was highlighted in a letter to The Times in March 1919, under the heading ‘Nurses Dismissed Summarily’ and signed by ‘Q.A.I.M.N.S.R. Members.’

Sir - The members of Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (Reserve) would like to bring before the public the unfair way in which they are being demobilized. They are being given 48 hours' notice, and after that pay and allowances cease. Many of us have served now for four years, and, never having had proper holidays are unfit to start work again immediately. We are a body of women working for our living, and are not in a position to be dismissed at so short notice. Many have no parents or homes, and will have to go into lodgings and pay for them. Are we not entitled to some consideration in the form of one month's wages and allowances in lieu of a month's notice? The War Office expects one month's notice from anyone leaving the Service and the extra £20 added to our salaries in September, 1916, had to be refunded.[248]

The next day’s edition brought a quick response from a long-serving member of the Territorial Force Nursing Service, Mary Hines:

Sir - May I be allowed to comment on the letter re the 'scandalous' treatment of Army nurses which appeared in The Times of yesterday. I have been a member of the Territorial Force Nursing Service since 1914, and although I am well aware that the Army is competent to speak for itself, I feel it is only fair to let the general public know how well I consider we have been treated, and how little cause there is for grievance. Sisters and nurses in the Army rank as officers. They are thus, according to King's Regulations, liable to be demobilized at 24 hours' notice, and are entitled to no unemployment pay. When the armistice was signed our matron warned us that we might be demobilized any day, and advised us to look for other posts at once. Some of our members procured posts and have already been released. One has only to glance down the columns of the nursing papers to see the great demand there is for nurses. Surely some post can be accepted until something really suitable is found, to keep a homeless nurse from want. But why, after being in Army employ so long, should there be no savings to fall back on?

Comparing it with civil pay the Army pay has been good. In 1916, in consideration that we agreed to remain in the Army as long as our services were required, an additional annual £20 was added to our salary. We have also good allowances, half-fare vouchers, and, upon occasion, warrants, which in these days of expensive travelling are a great help. The yearly gratuity is assured, in the case of a sister £10 and in that of a nurse £7.10s., both of which I hear may probably be increased. Furthermore, we joined the Army not only for a livelihood, but also from a sense of loyalty to our country, as our menfolk have done. It is a privilege not granted to all to have been allowed to serve at the front. Extra field allowance has been paid. Why then grumble at the hardships endured?[249]

The main demobilisation hostel for British nursing staff leaving France in 1919 was the Marine Hotel, Boulogne. Having left their medical unit women might stay there for some days waiting for the relevant forms to be completed and permissions granted before finally obtaining a passage across the Channel. Once in England they were transferred to the Nurses’ Dispersal Hostel, sited in a Folkestone hotel, for an overnight stay and final processing. If disembarking at Southampton, they were received at the Dispersal Hostel, Brockenhurst, and with them went an assortment of forms. Although different versions were used, they always included:

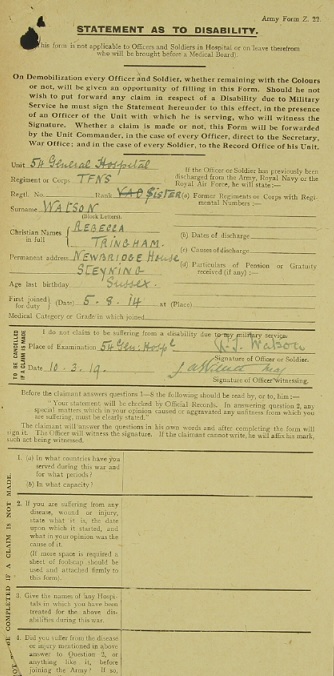

Form Z.26, Dispersal Certificate, completed in France (or other theatre of war) and over-stamped with the actual date of demobilisation at the UK dispersal hostel.

Dispersal Certificate for Rebecca Watson [The National Archives, WO399/15368]

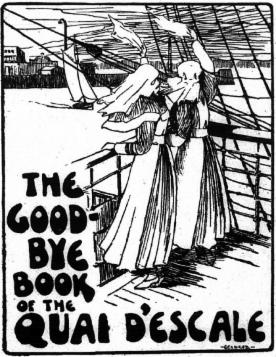

Form Z.22, ‘Statement as to Disability,’ was signed to indicate that the person named considered themselves fit and had no disability attributable to military service. This ensured that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to later make a claim for pension due to illness caused whilst serving. If disability was claimed, the form was completed with full details of the relevant sickness or disease and a medical board arranged for assessment of the condition outlined. It is rare to see forms claiming disability on demobilisation from France as if a woman already considered herself unfit, it is unlikely that she would be routinely demobilised from overseas.

Rebecca Watson confirming that she is not suffering any disability on discharge [The National Archives, WO399/15368]

Form Z.25, a record of the insurance contributions due, and the Society to which they were to be paid.[250]

Form W.3165, the claim for war service gratuity. Length of service was estimated in an exact numbers of years and days, in order for the gratuity to be paid on a pro-rata basis.[251]

All British trained nurses were also instructed to ‘report in writing to the Secretary, Nurses’ Demobilisation and Resettlement Committee, 16 Curzon Street, Mayfair, as well as to the War Office’.[252]

Many nurses from Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa were attached to Q.A.I.M.N.S. Reserve and the T.F.N.S. If they had initially travelled to the United Kingdom with the intention of offering their professional services to the War Office, they could ask to be repatriated to their country of origin at Government expense. Nurses already working in the UK prior to the war were not usually eligible on the grounds that they had come to the country to work before the outbreak of war and were therefore responsible for their own return arrangements as they would have been in peacetime. In these cases their wartime contribution, often more than four years, was conveniently overlooked. The decision-making in all cases was quickly delegated to a special department:

Received ruling from War Office to the effect that all members of the Q.A.I.M.N.S.R. who wish to apply for a passage to Australia or South Africa should apply in writing direct to the Officer in charge Repatriation Records, Winchester, where all claims are being dealt with for return passages.[253]

Mildred Rees was an ‘energetic, reliable, conscientious and hard-working’ nurse from New Zealand who served with the Q.A.I.M.N.S. Reserve for four years and fifty-five days, but was refused a passage home on the grounds that she had arrived in England to work prior to January 1st, 1914. She was employed by the Hampstead and Mayfair Nursing Corps from February 1910, so although there were perhaps grounds for her to make her own way home, places on transports were in very short supply for civilians and her long period of satisfactory employment might be seen as deserving of some reward.[254] Others who travelled independently and later requested a refund of their travelling expenses were asked to provide proof of their date of arrival together with receipts proving that they had met the cost of the fare themselves:

Received War Office letter requesting that Sister A. I. Z. Brizzell, Q.A.I.M.N.S.R. should obtain and forward if possible receipt for payment of passage from South Africa to the United Kingdom, when her claim will be considered. It was regretted that no definite ruling could be given on this subject. Each case is to be referred for consideration and all applications for refund of passage money to be accompanied by a receipt from the Steamship Company.[255]

In many cases it seems that the War Office took every step possible to avoid meeting the cost of both travel to the United Kingdom and repatriation, and many women soon realised that their entry into the war was rather simpler than their exit from it, making ‘home’ seem a very long way away in the spring of 1919. Nurses awaiting repatriation were first returned to England and accommodation found for them in either hostels or nurses’ homes in and around the capital. In some cases temporary posts on the staff of military hospitals were offered until a passage could be arranged. During this waiting time they were still under contract to the War Office and received pay and allowances, the actual date of termination of contract being eight days after embarkation for those returning to Canada, twenty days to South Africa and thirty-six days after embarkation to Australia.

As the run-down of hospitals and casualty clearing stations in France continued in the months after the war, nurses, both trained and untrained, continued to be demobilised in line with the reduction in establishment. In March, 1920, the last month for which the war diary of the Matron-in-Chief in France & Flanders was completed, ten women were demobilised, leaving just fifty-three trained and twenty-one untrained nurses remaining in France.[256]

*****

[243] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 2 January 1919

[244] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 13 March 1919

[245] There numerous occurrences of this in the War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, but as an example, see WO95/3991, 7 March 1919

[246] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO953991, 14 January 1919

[247] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 18 January 1919

[248] The Times, 19th March 1919

[249] The Times, 20th March 1919

[250] Examples of Army Forms Z.25 and W.3165 can be found in the previous section ‘Leaving.’

[251] Details of the 1919 increase of gratuity, payment of War Bonus and new pay scales is outlined in section six ‘Pay’

[252] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 27 February 1919

[253] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 17 February 1919

[254] Service file of Mildred Gertrude Rees, The National Archives, WO399/6913

[255] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 18 February 1919

[256] War Diary of the Principal Matron in France, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 31 March 1920