THE FAIREST FORCE

2. THE RESERVES

*****

In 1897 Princess Christian’s Army Nursing Service Reserve [PCANSR] was formed to support the Army Nursing Service, the predecessor to QAIMNS, and members were used to supplement the permanent staff of military hospitals at home and abroad. After the formation of QAIMNS in 1902 the relationship between the two services was uneasy, PCANSR being an independent service under the direct control of the War Office but with no official connection to QAIMNS.[14] A permanent Reserve for QAIMNS, Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve, was formed in 1908, and from that time members of the PCANSR were no longer employed in military hospitals. Recruitment to PCANSR ceased and the running down of the service was anticipated. Yet in September 1914 there were still 337 names on the roll and a number of these women mobilized wearing the uniform of the QAIMNS Reserve but still officially part of the PCANSR. During the course of the Great War all mobilized members signed contracts to serve as members of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve, finally bringing to a close Princess Christian’s own nursing service.

From May 1908 nurses were invited to join the new Reserve for QAIMNS. It was intended that it be held at a constant 500 members and used to fill gaps in military hospitals at home caused by the under-establishment of the regular service, and in the event of war would be available to provide, at short notice, suitable nurses to supplement QAIMNS. Women who applied to join were graded in order to identify those who were suitably qualified in all respects to be appointed to QAIMNS if the need arose. Members were required to sign a contract for a period of three years and were paid a retaining fee of £2 per annum, and if actually employed received allowances on the QAIMNS scale appropriate to their rank.[15] In the event, recruitment was slow and patchy and in similar fashion to the regular branch, although many nurses applied, most were rejected. Although reasons for rejection are not given it seems likely that they were similar to those which resulted in being turned down for QAIMNS itself, i.e. insufficient nurse training; training at a hospital not approved by the Board, or failure to meet the educational and social standards set.

By July 1909 the Nursing Board were aware that recruitment was not going according to plan, and recommended that ‘advertisements should be placed in the leading papers, and articles written to the Nursing journals,'[16] but this had little effect and a year later the Board put on record their concerns, advising that other channels must be pursued:

Decided that the present unsatisfactory state of the Q.A.I.M.N.S. Reserve should be brought to the notice of the Secretary of State, with a recommendation from the Board that as the present system, which has been made trial of for 21 months, has failed to provide the required numbers, further efforts should be made by applying to the civil hospitals in the United Kingdom, with a view to ascertaining what number of nurses each hospital would be prepared to supply in the event of war.[17]

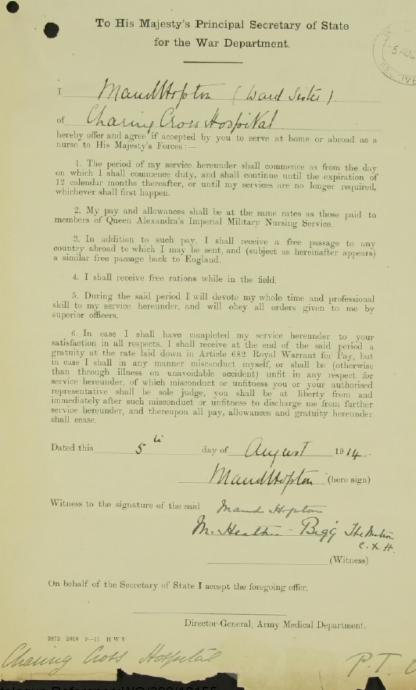

This decision brought into being the Civil Hospital Reserve [CHR], a group of trained nurses from throughout the United Kingdom vetted and recommended by their civil hospital matrons and each one willing to mobilise with the military nursing services in case of any future war. Although no known register of CHR members survives, individual service records usually indicate if a woman was mobilised as part of the Civil Hospital Reserve, and give the hospital of origin. These nurses wore the uniform of QAIMNS Reserve, initially without a service badge, and as the war progressed the majority transferred to the Reserve itself.

Initial contract for Maud Hopton from Charing Cross Hospital showing that she mobilised with the CHR on 5th August 1914 while at work, her form signed by her Matron, Miss Heather-Bigg [The National Archives, WO399/12155]

The Nursing Board drew a line under its failed QAIMNS Reserve in April 1911 when it recommended:

That after the required number of nurses for the Reserve are guaranteed by the civil hospitals, the present system of obtaining nurses be abolished. Those members, however, of the Q.A.I.M.N.S. Reserve already engaged will continue to serve under their existing arrangements. [18]

That line was to be only temporary, and wartime would change methods of recruitment and appointment once again.

While QAIMNS Reserve struggled, its sister service, the Territorial Force Nursing Service, flourished. The Territorial Force Nursing Service (TFNS) was established by R. B. Haldane in March 1908 following the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act (1907) and was intended to provide nursing staff for the twenty-three territorial force general hospitals planned for the United Kingdom in the event of war.[19] Across the nation women were clamouring to find some way of being included in any preparations for a future war and the service proved attractive, for at that time they claimed to be the only group of women with a defined part to play in national defence.[20]

Members of No.3 Southern General Hospital, Oxford (TFNS) [courtesy of Judy Burge]

Hospitals were allocated a staff of ninety-one trained nurses and, allowing for the fact that some members might hold positions in civil life that prevented their immediate mobilisation, 120 women were recruited for each; two matrons, thirty sisters and eighty-eight staff nurses. The nursing staff of each hospital was under the control of a Principal Matron, a senior civil nurse already based in a local general hospital and who continued to fulfil her usual duties in addition to the administration of the territorial unit. This provided a total establishment of 2,760 women who in peacetime went about their normal duties in civil hospitals and private homes but with a commitment to the War Office and holding mobilization orders. [21] The Standing Orders for the TFNS closely mirrored those of QAIMNS and the standards of entry were similar. The insistence on a full three year nurse training in an approved hospital remained, though it seems likely that when appointing staff rather more emphasis was put on professional ability than on social standing.

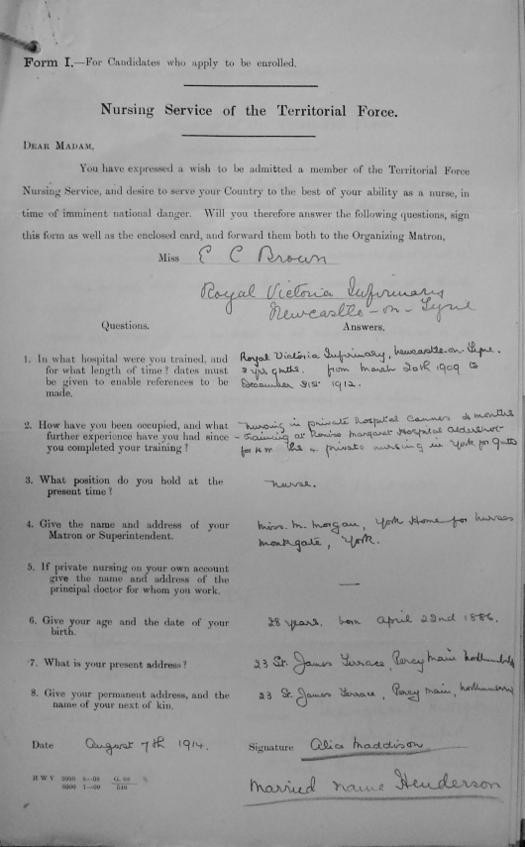

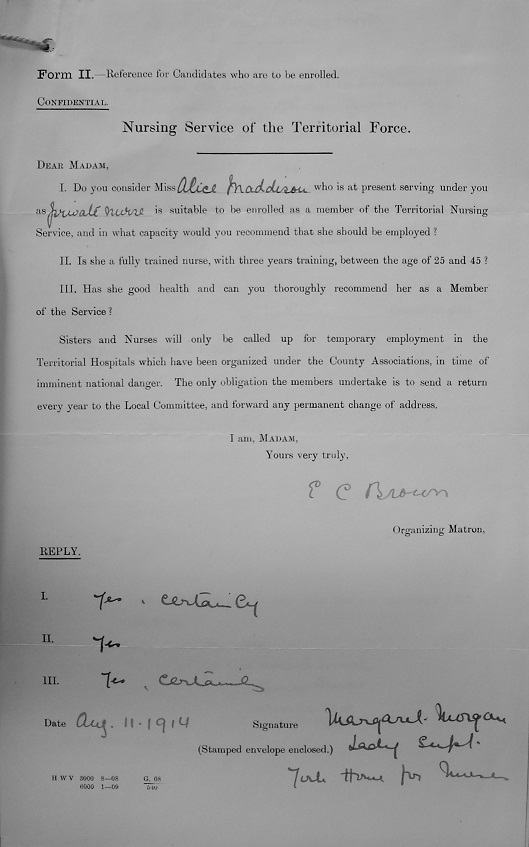

Unlike members of QAIMNS Reserve who were recruited centrally by the War Office, most applicants to the TFNS were interviewed by the Principal Matron and a local committee in the area of the hospital they wished to join. Although about three-quarters of QAIMNS service records contain original application forms, a sample of which can be seen here, these are invariably absent in files for members of the TFNS. It’s not known whether this was due to a different process during the weeding process of the 1930s when they were stripped of much of their content, or whether the forms were always retained locally following the interview and acceptance process. If the latter is true, there may still be some held in archives in towns which were home to territorial force hospitals during wartime. Luckily a tiny number can still be found in service records:

The National Archives, WO399/13126, service record of Alice Maddison

Although originally intended for home service only, in 1913 members of the TFNS were given the opportunity to notify their intention of willingness to serve overseas if required.[22] The sudden need for a large number of nurses to accompany the British Expeditionary Force to France in 1914 resulted in some members proceeding overseas during the early weeks of the war. Due to the pre-war approach of forming complete hospitals with nurses of all grades, many of the TFNS nurses had long experience in nursing, holding positions of great responsibility in civil life. Among them were women who were working as assistant matrons and senior sisters in some of the United Kingdom’s great institutions such as St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London and the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, and these women coped admirably with the management of large military hospitals. They quickly adapted their skills to meet the new and complex needs of casualty clearing stations and field ambulances, becoming some of the most able nurse-managers in wartime.

Standing Orders for the Territorial Force Nursing Service can be found on the following page, and include details of organisation, conditions, pay, uniform and duties:

Standing Orders for the Territorial Force Nursing Service

More about these Reserves and how they fitted into the wartime service can be found on the page 'Mobilisaton'

For a further overview of the British military nursing services in wartime see this 2010 article:

British Military Nurses and the Great War - A Guide to the Services

For a fuller outline of the Territorial Force Nursing Service see:

The Territorial Force Nursing Service 1908-1921

*****

14. For more details of the pre-war services see ‘Angels and Citizens – British Women as Military Nurses 1854-1914’ Anne Summers, Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., 1988

15. The National Archives, WO243/26, p.5, A Scheme for the Organization of a Reserve of Nurses, 13 May 1908

16. The National Archives, WO243/27, Minutes of the Nursing Board of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, 10 November 1909

17. The National Archives, WO243/28, Minutes of the Nursing Board for Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, 1 June 1910

18. Ibid., 5 April 1911

19. Later in the war two more Territorial Force General Hospitals were opened bringing the total to twenty-five

20. The Times 16th March 1909, p. 9

21. Standing Orders for the Territorial Force Nursing Service, 1908

22. The National Archives, WO123/55, Army Order 92, March 1913