THE FAIREST FORCE

17. DISCIPLINE AND BAD BEHAVIOUR

*****

There is much emphasis in every area on portraying nurses who served in wartime as ‘angels’ and ‘heroines.’ Writers, publishers and television producers work hard to promote this image knowing that it has wide audience appeal and is a factor in getting good sales and first-class reviews. It’s not a view I’ve ever subscribed to and now find myself working hard to show it as at best fanciful and at its worst, counter-productive in representing nurses as hard-working and experienced professionals. Angels, in whatever form, are no good at all at changing sheets, preparing food and tending wounds.

During the Great War the women who formed the staff of hospitals both at home and overseas were a broad range of normal women, good, bad and indifferent. In general, trained nurses came from every section of society, had received one form of education among many, and then gone on to spend three years undertaking nurse training in the widest variety of institutions that the United Kingdom could offer. Owing to an immense shortage of trained nurses, the strict pre-war insistence on employing only women of high social status within the military nursing services was set aside, although as before, the necessity to be fully-trained remained. Within this wartime mix women brought with them a wealth of different backgrounds, personalities, temperaments and experiences, and reacted to military life and the conditions of ‘active service’ in a variety of ways. Discipline for nurses had always been strict to a degree which might be regarded as uncalled-for and unnecessary, and that it should continue into wartime was thought to be entirely acceptable.

Sister Catherine Black

Catherine Black, later a member of QAIMNS Reserve, wrote of her experiences as a probationer at The London Hospital, Whitechapel when she started her training in 1903:

As individuals we hardly counted, as members of a body ruled with an almost military discipline we were important. Our hours on duty would hardly be tolerated by any nurse in these days, [1939] but there was no appealing against them then. We were called at 6 a.m., breakfasted at 6.30 a.m. (a boiled egg, lukewarm, a sardine or a piece of potted meat, thick bread and butter, weak tea, and anyone who was five minutes late got a black mark. Five black marks in a quarter and you lost one of your cherished days off). Into the wards at 7 a.m., on duty till 9.20 p.m. You slept usually in a number of dilapidated houses huddled together at the back of the hospital and familiarly known as ‘The Rabbit Warren.’ I remember I recoiled in dismay when I was first shown my dingy little basement room, so dark that the gas had to be kept lighted in the daytime, so damp that the paper was peeling off the walls, so cold in winter that as a great concession I was allowed a fire provided I carried the coals myself.[207]

If conditions were such in the most prestigious of London teaching hospitals, Army service matched and exceeded them with regard to discipline. In 1901, while working at Station Hospital, Alexandria, two members of the Army Nursing Service were severely disciplined for playing cards with an officer in their rooms after midnight, their sins noted by the soldier on duty at the gate. The senior Medical Officer wrote:

I had an interview with Sister Fletcher on the subject. She did not deny the correctness of the entries in the ‘Gate Book,’ and maintained very much her position detailed in her explanation. The file speaks for itself, in my opinion such conduct is a gross scandal, even fully granting there is no question of immorality.[208]

The final result of this misdemeanour was that neither Miss Fletcher nor her colleague were accepted for transfer to QAIMNS when it was formed the following year and were forced to resign.

This type of reaction to a skewed perception of how middle-aged, single, professional women were supposed to behave was virtually unchanged when war arrived more than a decade later. Behaviour considered unacceptable by the military authorities in relation to the nursing staff took a multitude of different forms. It would be possible for the myriad of occasions outlined in the war diary of the Matron-in-Chief alone to form a book on their own account. Many revolve around minor grievances; the wearing of unauthorised uniform, unpunctuality and returning late to camp. Today these might be regarded as the sins of a teenage girl but the women involved a hundred years ago were all over the age of twenty-three and the majority in their thirties, forties and upwards. However, other things went rather deeper and were considered more serious. The War Office considered itself ‘in loco parentis’ of nurses overseas and felt it had a responsibility not only to the women themselves but more importantly to their parents and relatives. In line with their colleagues at the turn of the century, what constituted ‘immorality’ was often based upon one personal opinion rather than founded in known fact. Ambulance trains seem to have provided an ideal breeding ground for relationships to blossom:

To Puchevillers first to enquire into the irregular behaviour of the Nursing Sisters on trains whilst waiting there. Found the matter was even worse than at first thought, and that the matter had again been reported through another channel. Told Col. Huddleston that his report is being sent to DG for transmission to L of C when the matter would be seriously dealt with.[209]

And three days later the Matron-in-Chief reported:

Saw A/Sister A. R. Newby, Q.A.I.M.N.S.R., who has recently been taken off a train in consequence of her intimacy with an orderly. She was transferred to No.2 Stationary Hospital, and as I heard that she had been in the habit of meeting him and walking about the camp with him, I sent for her. She told me that she was going to be married to him and that he had written to her people and they wished to be married at the earliest opportunity. I advised her to apply for a transfer to the Home Establishment.[210]

In this case available records show that Ada Newby did indeed marry a private soldier of the Royal Army Medical Corps the following year and became Mrs. Rapp.[211]

August 1916 was a busy month for Miss McCarthy in dealing with matters of a personal nature. A few days before her encounter with Miss Newby she was asked by the Director-General of Medical Services to enquire into a problem at No.20 Field Ambulance:

After lunch I went to 20 Field Ambulance to see a Staff Nurse Weatherstone who had sent in her resignation, in consequence have being on too intimate terms with the Sergeant-Major, who she did not know was a married man. He had been moved. The DG wished me to go into the matter. Found her to be a respectable woman of the servant class. Trained at Edinburgh, where she had been on the Staff for 4 years. Very upset about the whole thing. Recommended her to write explaining the matter, and asking if her case might have favourable consideration and her resignation to be withdrawn. She implored me to give her another chance, which I should never regret. Left under the understanding she would write and the matter should be considered.[212]

A service file survives for Miss Weatherstone at The National Archives but her misdemeanours at this time are not mentioned.[213] Following the incident she was immediately transferred to a base hospital and during the rest of the war she served with distinction in hospitals, casualty clearing stations and on an ambulance train, receiving the Royal Red Cross (1st Class) in June 1918, an infrequent honour for a Staff Nurse and a sign that her work was both recognised and appreciated. This ‘respectable woman of the servant class’ was given the chance she so earnestly requested and gave no-one cause for any regrets at the decision made.

Mentions of nurses becoming pregnant while actively employed in nursing duties are rare, the subject being treated with some diplomacy. Considering the number of married women employed it cannot have been an uncommon occurrence, but in these cases the grounds for resignation were usually noted in official records as ‘personal reasons.’ However, the inexact science of reading between the lines can sometimes be usefully employed in finding evidence of the manner in which pregnancy among single women was treated and reported. In July 1917:

S/Nurse H. Griffiths, Q.A.I.M.N.S.R., who has been doing duty on a barge, requested a private interview with me. This lady has been given 7 days’ special leave and told to report to the Matron-in-Chief, War Office, on arrival in England, pending the acceptance of her resignation. Confidential notes have been forwarded to the Matron-in-Chief, and it is hoped that her marriage will be arranged shortly.[214]

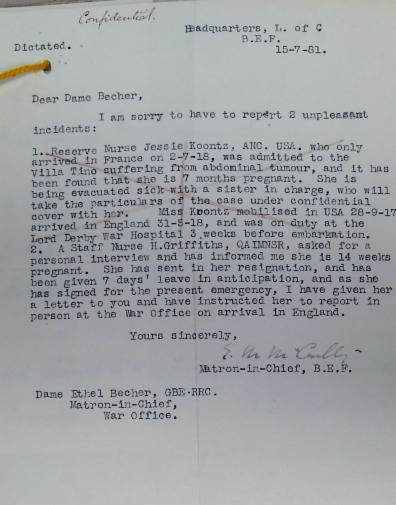

The service file of Hannah Griffiths ‘a very capable and trustworthy Sister’ is more enlightening on the subject than could have been hoped for. It shows that immediately following this interview Miss McCarthy wrote to her counterpart at the War Office, Ethel Becher. The original letter, dated the following day, is included in the file. Not only does it throw light on Miss Griffiths’ condition but also details of another case:

I am sorry to have to report 2 unpleasant incidents:

1. Reserve Nurse Jessie Koontz, ANC, USA, who only arrived in France on 2-7-18, was admitted to the Villa Tino suffering from abdominal tumour, and it has been found that she is 7 months pregnant. She is being evacuated sick with a sister in charge, who will take the particulars of the case under confidential cover with her. Miss Koontz mobilised in USA 28-9-17, arrived in England 31-5-18, and was on duty at the Lord Derby War Hospital 3 weeks before embarkation.

2. A Staff Nurse H. Griffiths, QAIMNSR, asked for a personal interview and has informed me she is 14 weeks pregnant. She has sent in her resignation, and has been given 7 day’s' leave in anticipation, and as she has signed for the present emergency, I have given her a letter to you, and have instructed her to report in person at the War Office on arrival in England.[215]

A copy of the letter in the service file of Hannah Griffiths mentioned above [The National Archives, WO399/3364]

There were occasions when actions taken by military nurses in France, though probably committed in innocence, brought them to the notice of the intelligence services. In September 1915, a Miss Matthews, working at a casualty clearing station in Bailleul, was asked to receive parcels from England on behalf of a local shopkeeper and forward them on to him which she did for some time. When she left the unit she asked a colleague, Miss Jolly, to continue this service and it was only when a parcel in transit was opened that some illegal activity was discovered. Although the cause for suspicion is not noted, the shopkeeper was tried by the military authorities but fortunately for the nurses their behaviour was put down to ‘kindness of heart’ and no further action taken.[216]

Less lucky was Staff Nurse Winifred Rooney, thought to be guilty of having strong connections with Sinn Fein and for communicating with the enemy:

Received a telephone message from the A.A.G. saying that he had been up to Headquarters at 5 o’clock to see me on a matter of importance. Found that he wished to let me know that a certain S/Nurse of the name of Rooney Q.A.I.M.N.S.R. had been found carrying on correspondence with the enemy. She was thought to be a Sinn Feiner, and it was probable that she would be tried by Court Martial. He wished it to be entirely confidential until the official information came to Headquarters. He did not wish it talked about.[217]

This nurse’s service file held at The National Archives outlines in detail the investigations that followed.[218] She was accused of passing messages and letters to German prisoners of war working in Rouen together with ‘comforts’ of cigarettes and chocolate and newspaper cuttings concerning German Internees in Ireland. Miss Rooney was also seen signalling with ‘two handkerchiefs, one green and one white, in a peculiar manner,’ the implication being that green and white were colours associated with Sinn Fein. However, it was considered that there was insufficient evidence to warrant a court-martial. In order to avoid any legal action or publicity, she was returned to the United Kingdom and as her contract had rather conveniently reached its date of expiry it was not renewed, thus relieving the Army of the problems associated with dismissal.[219]

Over the course of the war many nurses felt restricted by their confinement to the relatively small area surrounding their units and the absence of any chance to visit more forward areas. Most accepted this without question but some of the more adventurous sought ways to take illicit trips to places forbidden to them. With the fighting still fierce around the battlefields of the Somme, Miss McCarthy was alarmed to hear a report of nurses placing themselves in danger:

Had lunch at Headquarters, where I saw the D.M.S. … Told him of a report which I had heard that 3 Nursing Sisters had been seen at Fricourt looking at German trenches with heavy shell fire going on. He agreed with me that drastic measures must be taken and undertook to issue instructions to all his Clearing Stations that Nursing Sisters were not permitted to go further forward than where they were at present stationed.[220]

These three women were lucky that their identity remained a mystery but another, Miss Waite, did not fare so well.[221] As the Sister-in-Charge of No.7 Ambulance Train she frequently found herself with ‘waiting time’ while the train was not taking on or discharging casualties. On one occasion her activities resulted in her being summoned to the office of the Matron-in-Chief to explain her behaviour:

Miss Waite TFNS, Sister in Charge, 7 Ambulance Train, came to report that when at St. Pol and she found that the train was not leaving for 36 hours, she got permission from the OC to be off the whole day, not saying where she was going. She started early with the intention of getting if possible to Arras, some 30 miles. She had no permit … passed sentries, got lifts and eventually got into Arras, having arranged with a driver of one of the convoys who was leaving at 5pm to drive her back, but when she was leaving, and had got into the lorry, she was stopped by an officer, put in his car, driven to St. Pol, where she was arrested under suspicion. While she was here the official report arrived. I pointed out how dreadful the whole thing was, the irregularity, and how even at the Bases nurses are not allowed to leave their areas. She quite saw the point, and regretted the indiscretion, but she kept adding it was most interesting.[222]

Three days’ later Miss Waite was left in no doubt about the seriousness of her actions:

She was to be moved to a Base Hospital and that she should be informed that any further disregard of orders will entail her services in France being dispensed with. Wrote to her privately, ordered her to 1 General Hospital Etretat and sent the information officially to the Base.[223]

Going to dances, either in their own Sisters’ Mess, or in other Messes by invitation, was strictly prohibited for all British nursing staff, and the history behind this rule is given in the previous section, ‘Off Duty.’ While there is little doubt that it happened frequently, getting caught could lead to the most draconian of punishments. In July 1917, two VADs, Miss Child and Miss Fairhead of No.20 General Hospital, Camiers, were found to have attended a dance given by officers of the local Machine Gun School in Etaples. They were summoned to Miss McCarthy’s office in Abbeville to explain their actions and discover their fate:

Miss Child and Miss Fairhead, V.A.D. members, came to the office for an interview. I pointed out the seriousness of their offence and gave them the choice of sending in their resignations or applying to transfer to the Home Establishment. Miss Child chose to resign and Miss Fairhead to transfer to Home Establishment.[224]

Within two days Miss Child and Miss Fairhead were back in the United Kingdom, and all the associated paperwork forwarded to the office of the Director General of Medical Services, Sir Arthur Sloggett, for his approval. However, a married man with a daughter working as a VAD in France, he took a far more lenient view of what he considered a rather trivial matter. On the 22nd September, the paperwork was returned to Abbeville:

D.G.M.S. returned applications of Miss Child, V.A.D. and Miss Fairhead, V.A.D., the former to resign, the latter to be transferred to Home Establishment, saying that in future such cases should be referred to him before action is taken.[225]

In her usual form, Miss McCarthy immediately made arrangements to discuss the matter with him:

Visited G.H.Q. to see the D.G.M.S. with reference to the recent incident where 2 V.A.D.’s from 20 General Hospital had been reported on for being absent without leave from dinner and for not coming in until 10 o’clock, they having attended a dance at the Machine Gun Officers’ Training School. When the report was sent to D.G.M.S., he thought that I had dealt with them in rather a severe manner – but when I had seen him and explained that these ladies thoroughly understood that it was against the regulations, that they had not asked the Matron’s permission as they knew she would not give it, and that they had absented themselves from dinner also without permission, he realised that it was a matter which could not be passed over lightly. I told him that I had given them the opportunity of either transferring to Home Establishment or resigning. One had asked to resign and the other to be transferred.[226]

Her point made, she must have taken the words of the Director General seriously, as just two days after their meeting she interviewed two more VADs who had broken the same rule but this time with a rather different outcome:

Miss Durst and Miss Brown, V.A.D. members, came to the office to be interviewed with reference to their conduct in attending a dance given by officers in the Etaples area. These ladies have been posted for temporary duty at 2 Stationary Hospital Annexe and the Matron has been instructed to send in a report on their work and conduct.[227]

No.2 Stationary Hospital Annexe was the Sick Sisters’ Hospital for the Abbeville area, so far removed from any men and also very near to the watchful eye of the Matron-in-Chief. The case of Miss Child and Miss Fairhead is the last time that the diary records any nurse being asked to resign due to having attended a dance. It appears that Miss McCarthy was prepared to defer to the Director General and take a more relaxed attitude to incidents of this type, though falling foul of the rule was still likely to reap some sort of unwanted reward.

In the spring of 1919 trips were arranged for nurses to visit the towns and battlefields destroyed by the war. These could only be made available to a relatively small number of women, but many more wanted to be included and when it was not possible officially a few managed it unofficially. While waiting in Boulogne for the demobilisation process to claim them, several groups of women found the means to make their own way to forward areas. Most made their intentions known at least to their colleagues, but considering the problems with transport existing at the time one woman managed a few days of some note. I suspect that despite the consequences it was a trip that she looked back on in later life with pleasure rather than any regret.

Reported to D.M.S., L. of C. and A/Provost Marshal Boulogne, that Miss D. Armstrong, V.A.D. who reported at the Marine Hotel on the 28th for demobilisation, has not been heard of since that date. The Matron of the Dispersal Hostel, Folkestone, states that she has not reported there.[228]

She eventually returned after an absence of more than five days:

Wired DGMS that there was no trace of Miss D. Armstrong, VAD since 28th ult. She was still missing. Next of kin: Father Charles Armstrong, Eastfields, Peterborough. Wired later to say she had returned today. Forwarded to DGMS, DMS L of C and A/Provost Marshal, Boulogne, statement written by Miss Armstrong in explanation of her absence from the Hotel Marine without permission from the morning of March 28th till the evening of April 2nd. This lady proceeded to the UK on demobilisation on April 3rd. She is not recommended for further service. Miss Armstrong left Boulogne on Friday 28th and spent the night at Dunkirk, the following two nights at Lille, the night of the 31st at St. Quentin and the night of April 1st at Amiens.[229]

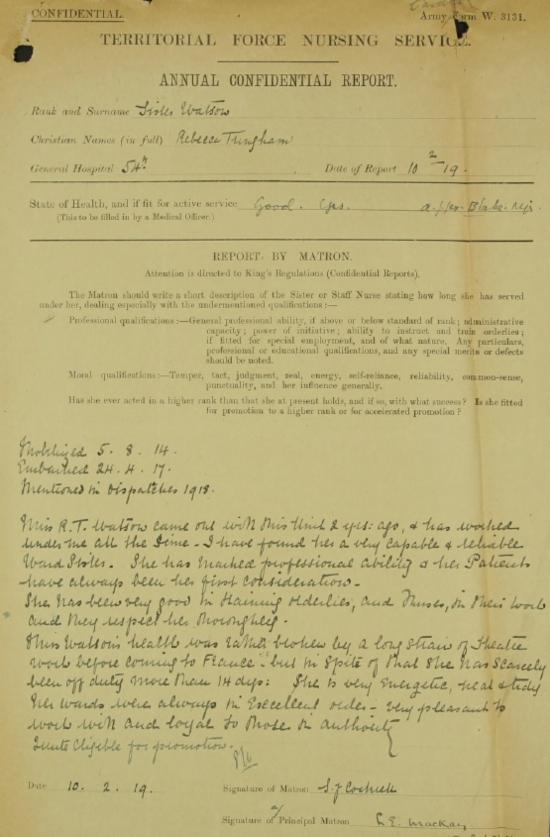

While serving in France and Flanders all nurses, both trained and untrained were reported on by their senior officers yearly, or whenever leaving one unit for a transfer or posting to another – this was their ‘Confidential Report.’ As many nurses moved unit with great frequency, the writing of these reports was a heavy responsibility for their Matron or Sister-in-Charge, and also for the senior Medical Officer who also commented on, and signed them. Most confidential reports no longer exist in the service files of members of QAIMNS Reserve, though whether this was because they were retained elsewhere or destroyed during the weeding process of the 1930s is unclear. However, reports are abundant in the files of members of the Territorial Force Nursing Service and give a good insight into the personality and capabilities of the nurses themselves.

Confidential Report for Sister Rebecca Watson, TFNS, while at No.54 General Hospital [The National Archives, WO399/15368]

*****

[207] King’s Nurse, Beggar’s Nurse; Catherine Black; Hurst and Blackett, London, 1939

[208] Service file of Margaret Fanny Fletcher, The National Archives, WO399/4751

[209] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 29 August 1916

[210] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 1 September 1916

[211] General Register Office index of marriages via FindMyPast

[212] War Diary of Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 23 August 1916

[213] Service file of Anna (Joanna) Weatherstone, The National Archives, WO399/8797

[214] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 14 July 1918

[215] Service file of Hannah Griffiths, The National Archives, WO399/3364

[216] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3988, 19 September 1915 and 21 September 1915

[217] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3990, 11 June 1918

[218] Service File of Winifred Rooney, The National Archives, WO399/7197

[219 More about the case of Miss Rooney can be read on ‘This Intrepid Band’ here

[220] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 21 October 1916

[221] Service file of Lilian Julia Waite, The National Archives, WO399/15247

[222] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 23 June 1916

[223] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 26 June 1916

[224] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3990, 17 September 1917

[225] Ibid., 22 September 1917

[226] Ibid., 24 September 1917 (Visits)

[227] Ibid., 26 September 1917

[228] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 31 March 1919

[229] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 2 April 1919